The Lost World

In His Own Words

It [The Lost World] was really something that came from the readers. From the first publication of the book, kids began to read it and they would send letters: “What about the sequel? What about the sequel? What about the sequel?” I had not ever done a sequel before and would always say, “There won’t be one.” Then, as time went on, they would say, “Well, this would be a good sequel. Here’s another idea for a sequel.” Now you’re reading them thinking,”No, that’s not right. No, we wouldn’t do that.” Then you start thinking, “Well, why not? Well, what would be good?” Eventually there did seem to be the likelihood there would be another film and Steven seemed to have some interest in that. It’s a very difficult structural problem because it has to be the same but different; if it’s really the same, then it’s the same—and if it’s really different, then it’s not a sequel. So it’s in some funny intermediate territory.

Synopsis

Six years after the death of John Hammond and the mysterious destruction of his Jurassic Park island of Isla Nubla, mathematician Ian Malcolm discovers a second island off Costa Rica, where Hammond created his genetically bred dinosaurs. He travels there with a scientific research team including paleobiologist Richard Levine, Sarah Harding, and two stowaway kids, Kelly and Arby, both 11 years old.

Once on the island, they find themselves on the run for their lives from some of the killer dinosaurs with whom Ian has already crossed paths, along with some new killers. The group not only has to contend with the dinosaurs, but with murderous rival scientist Lewis Dodgson and his cronies, who are out to steal the dinosaur eggs for themselves, as well.

Passage 1

“It should be accurate,” Malcolm said. “You know, there is such a thing as accurate and inaccurate. Irrespective of whatever your feelings are.” He walked on, irratable, ignoring the momentary pain in his leg. The modeler annoyed him, although he had to admit Tim was just a representative of the current, fuzzy-minded thinking — what Malcolm called “sappy science.”

Malcolm had long been impatient with the arrogance of his scientific colleagues. They maintained that arrogance, he knew, by resolutely ignoring the history of science as a way of thought. Scientists pretended that history didn’t matter, because the errors of the past were now corrected by modern discoveries. But of course, their forebears had believed exactly the same thing in the past, too. They had been wrong then. And modern scientists were wrong now.

Passage 2

The tyrannosaur stood again, the car sprang back up, and Thorne saw thick white paste smeared across the hood. The tyrannosaur immediately moved away, heading down the game trail, disappearing into the jungle.

Behind them, they saw it emerge into the open again, stalk across the open compound. It lumbered behind the convenience store, passed between two of the cottages, and then disappeared from sight again.

Thorne glanced at Eddie, who jerked his head toward Malcolm. Malcolm had not turned to watch the departing tyrannosaur. He was still staring forward, his body tense. “Ian?” Thorne said. He touched him on the shoulder.

Malcolm said, “Is he gone?”

“Yes. He’s gone.”

Ian Malcolm’s body relaxed, his shoulders dropping. He exhaled slowly. His head sagged to his chest. He took a deep breath, and raised his head again. “You’ve go to admit,” he said. “You don’t see that everyday.”

Passage 3

But the velociraptors behaved differently. There was a disorderly, chaotic feeling to the scene before him: ill-formed nests; quarreling adults; very few young and juvenille animals; the eggshells crushed; the broken mounds stepped on. Around the mounds, Levine now saw scattered small bones which he presumed where the remains of newborns. He saw no living infants anywhere in the clearing. There were three juveniles, but these younger animals were forced to fend for themselves, and they already showed many scars on their bodies. The youngsters looked thin, undernourished. Poking around the periphery of the carcass, they were cautious, backing away whenever one of the adults snapped at them.

From the Archives

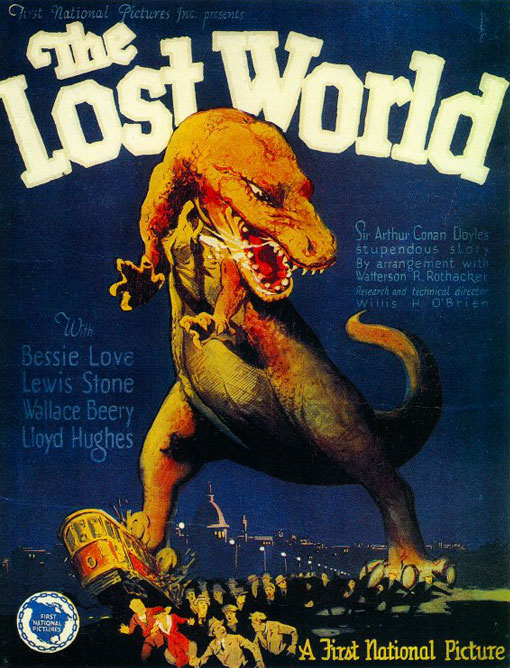

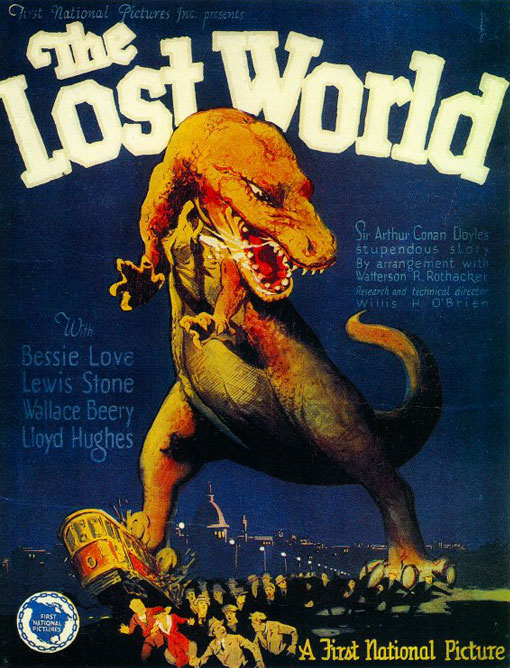

The Lost World was the only sequel Michael Crichton wrote, and he saw it as a challenge. The title was of course a reference to Arthur Conan Doyle, whose 1912 novel told of explorers visiting a remote plateau to confront dinosaurs. Michael Crichton borrowed another trick from Conan Doyle’s sequels —he brought a character back to life. Conan Doyle resuscitated Sherlock Holmes, even though he fell to his death at the Reichenbach Falls; Michael brought back Ian Malcolm, a favorite of readers and filmgoers.

Subsequently Michael wrote an introduction to a re-issue of Conan Doyle’s original novel. He used the opportunity to explore how Conan Doyle had made the concept of dinosaurs persuasive, and how he had overcome various difficulties in the narrative. You can read his essay here.

In His Own Words

[On bringing Ian Malcolm back to life for The Lost World] Malcolm came back because I needed him. I could do without the others, but not him because he is the “ironic commentator” on the action. He keeps telling us why it will go bad. And I had to have him back again. […] As Mark Twain once said, “Reports of my death are greatly exaggerated.” But it’s also true that Conan Doyle (the original author of a book called The Lost World) pushed Sherlock Holmes of the Reichenbach Falls with Moriarity. And they were unquestionably dead. And after a few years, Holmes turned out to have made a miraculous recovery. So these things happen in fiction.

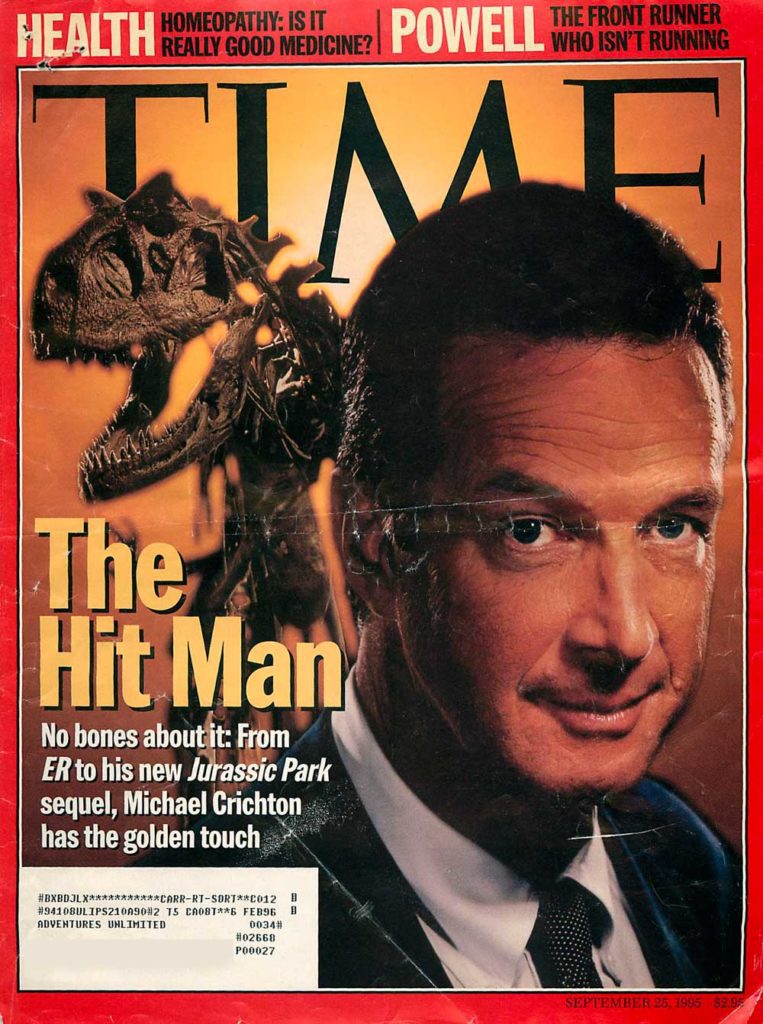

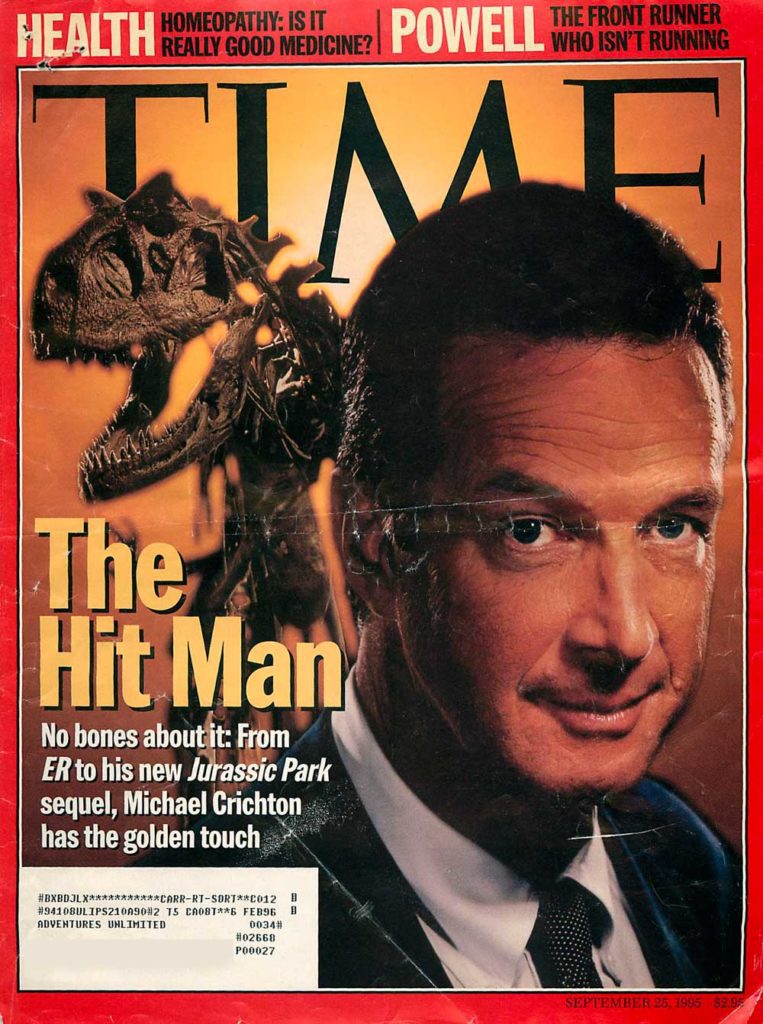

Michael Crichton and The Lost World were featured on the cover of Time magazine

In His Own Words

Why are people so interested in dinosaurs? Why are we so fascinated by these giant vanished creatures from the past? There are many reasons, but the I believe most compelling is that the dinosaurs confront us—directly and unavoidably—with the reality of extinction.

This has always been so. In the late 1700s, when giant animal bones were first dug up in Europe, they caused a crisis among scientists of the time. What could account for these bones? What animals did they represent? At first, scientists argued that the bones were the remnants of gigantic versions of animals now represented in smaller, contemporary forms. Most scientists thought that this explanation must be true, since God had created the world in the Biblical seven days—and God would never allow any of his creations to become extinct. The natural world at that time was essentially seen as a static, unchanging world. Individual animals might die, but whole species did not. Therefore it followed that these old bones could only represent variants of animals still alive.

But with further study, that early view proved unsupportable. These bones were not gigantic lizards or elephants. And in 1805, Baron Georges Cuvier, the most influential anatomist of his day, reluctantly concluded that the bones represented creatures that had become extinct. Cuvier believed that the extinctions had occurred as a result of world-wide catastrophes, akin to Noah’s flood. His theory, called Catastrophism, was hotly debated—and widely ridiculed—for decades to come.

Although Cuvier’s daring intellectual leap led to the eventual acceptance of extinction, his belief in catastrophe fared less well. The systematic study of geology in the nineteenth century led instead to a new doctrine, called Uniformitarianism, which argued that the earth changed gradually, and that extinctions had occurred slowly over time.

When Darwin proposed his theory of evolution in 1859, he built upon these ideas of gradual change. In the new Darwinian picture, there was little room for violent catastrophe. Indeed, in the post-Darwinian world, Catastrophism seemed to reflect the emotional turmoil of Cuvier and his pupil Agassiz, men who opposed evolution for religious reasons, and who were obliged to invoke violent upheaval to fit their beliefs to the geological record. For the next century, Catastrophism languished in the intellectual museum drawer reserved for Curious Outmoded Beliefs.

This was still the case when I was a university undergraduate, in the 1960s. As a student I studied evolution; it excited my imagination; and in fact my novel The Andromeda Strain was suggested by a footnote in George Gaylord Simpson’s scholarly text, The Major Features of Evolution. In those days, Simpson was an emeritus professor at Harvard, and on warm days he could be seen sitting on the steps of the Agassiz Museum, sunning himself like a wise old lizard. (I never had the nerve to go up and speak to him.) Simpson had pioneered the use of statistics in paleontology, and was one of the scientists leading the study of evolution into more rigorous mathematical analysis. So was my own professor, William Howells, who used complex computer programs to study of human evolution, and encouraged his students to do the same.

Even back in the 1960s, there was plenty of debate about evolution. It was understood to be an inherently contentious subject; when Louis Leakey gave a lecture at Harvard in 1963, scholars in the audience leapt angrily to their feet, shouting at him, and stalking red-faced from the auditorium. Feelings ran strong then—and they still do.

Many surprising developments in evolution have occurred in the decades since then, but to my mind none more unexpected than the sudden resuscitation of Baron Cuvier and his sleepy old doctrine of Catastrophism. After two hundred years of ridicule, catastrophe is again a topic of controversy, the subject of magazine articles and television specials. The immediate reason is the speculations of Luis Alvarez and his team on the possiblity that a metoric impact caused the Cretaceous extinctions that killed the dinosaurs. But underneath it all lies a deeper and peculiarly modern question—what makes any species become extinct?

As I began to write this novel, I found myself returning unexpectedly to the concerns of my undergraduate studies thirty years ago. Back then, evolution was so controversial that one quickly learned to write cautiously, justifying even the mildest statement with scholarly footnotes. If anything, evolution is more controversial today. And in its modern formulations, evolutionary theory is forbiddingly difficult, and frequently counter-intuitive. In The Lost World, I have been able only to touch on some of the most interesting trends in current scientific thinking, and to hint at the complexities of thought that lie beneath the surface of every point of view.

And, of course, there is an ever-present theological aspect. In an early draft of the novel, Ian Malcolm, heavily sedated with morphine, expressed his belief about the choice God had made in creating the world. Malcolm said that in his view, God might have created a perfect world of immortal creatures, where nothing ever changed. Such a world would be like an artist’s painting, perfect just as it was at the instant of creation, and never in need of change.

But evidently God had decided on a different sort of creation. Because instead, God had created a world where change occurred—where creatures were born, reproduced, and died. Where new generations took over, and replenished the earth. And therefore, Malcolm concluded, God must have believed in the importance of change. Not easy or frivolous change, because God’s world was inherently conservative, and it resisted change. But nevertheless, hard-won change did occur. So the fact of change was central in our God-given world.

But, Malcolm continued, nobody seemed to like that, or to accept it willingly. There were some people who refused to change anything for thousands of years. And other people who wanted to change every six months, like fashions. Either way was too easy, Malcolm said. Because God had created a world that was tougher than that. God’s world forced hard choices, and did not permit easy answers.

As originally written, Malcolm’s long tirade put the others to sleep. I cut it late in my revisions, because it just didn’t seem to fit. But I always liked the speech. And I remain convinced that the world we are born into is a world of controversy, and that it behooves us to respect our adversaries, and to honor them as expressing another aspect of God’s will.

Because in the end, evolution is a profound mystery. Life is a profound mystery. And we are fools if we forget that and think, even for a moment, that we know it all.

The Lost World (Movie)

| Release Date: | May 23, 1997 |

| Running Time: | 2 hrs. 9 min. |

| MPAA: | PG 13 |

| Director: | Steven Spielberg |

| Screenwriter: | David Koepp |

| Based on the Novel By: | Michael Crichton |

| Studio: | Universal Pictures |

| Starring: | Jeff Goldblum, Julianne Moore, Vince Vaughn, Arliss Howard, Pete Postlethwaite, Richard Attenborough, Peter Stormare, Richard Schiff |

The Lost World was the #3 movie of 1993.

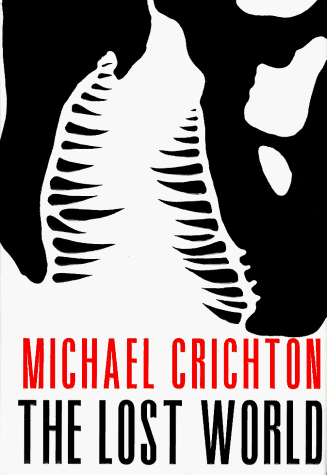

Book Covers