The Andromeda Strain

In His Own Words

I thought The Andromeda Strain was a great title, but for many years I had no book to go with it. I worked on draft after draft, never completing one, obsessing about the project. And all because I was so fond of the title I couldn’t abandon it.

The story itself was originally suggested by a footnote in George Gaylord Simpson’s scholarly work The Major Features of Evolution. Simpson inserted an uncharacteristically lighthearted footnote saying that organisms in the upper atmosphere had never been used by science-fiction writers to make a story.

I set out to do that.

Eventually I finished a whole draft and sent it to my new editor, Bob Gottleib, at Knopf. Bob said he would not even consider publishing it unless I was willing to completely rewrite it from beginning to end. I was twenty-five at the time, and Bob was only in his early thirties, but he had a very large reputation as an editor because he had edited Catch 22. So I gulped, and said I would rewrite it according to his directions.

Bob said that the novel should read like a New Yorker profile, that it should be absolutely convincing. I wasn’t really sure what that meant; I had read New Yorker profiles and found they varied widely. But he started me thinking about what The Andromeda Strain would look like, if the story were true. Where would I have gotten the information? How much would I know? And in what style would I write it, if it were true? I began to look at science non-fiction writing by people like Walter Sullivan, who wrote for the New York Times. And I began to imitate that factual, non-fiction writing style. It yielded a very cold, detached book that was also weirdly convincing.

After I sent Bob Gottlieb the rewritten manuscript, he called up and said I had done very good work, and therefore I only had to write half of it all over again. I gulped, and said I would. And after that, he would just call me every few days: rewrite the beginning of this chapter. Redo this description. This character isn’t right; fix it. Add a chapter here. And on, and on. I began to feel persecuted by these demands, which seemed interminable, and increasingly nit-picking. (I did not yet know how rare good editing is.)

When the book was published, lots of people thought it was true. It was pretty interesting. When Bob Wise set out to make the movie, his researchers assumed that everything was true, too, so they went out and found all the things the book talked about — the underground laboratory, the computer programs, the biometrics security. After a while I stopped telling people that I had made it all up, because it turned out that it was based on true things. But I didn’t know that when I was writing the book.

Synopsis

A military satellite returns to earth in northern Arizona. A team sent to recover the satellite breaks radio contact mysteriously. Because an infection is suspected, a team of scientists is sent to investigate, they find everybody in a small town is dead except for two survivors—an old man, and a screaming infant. These two, and the satellite, are taken to an underground laboratory where an organism called the Andromeda Strain is isolated, and nearly kills all of mankind.

The Andromeda Evolution

Synopsis

Fifty years after The Andromeda Strain made Michael Crichton a household name – and spawned a new genre, the technothriller – the threat returns. Deep inside Fairchild Air Force Base, Project Eternal Vigilance has continued to watch and wait for the Andromeda Strain to reappear. On the verge of being shut down, the project has registered no activity—until now. A Brazilian terrain-mapping drone has detected a bizarre anomaly of otherworldly matter in the middle of the jungle, and, worse yet, the tell-tale chemical signature of the deadly microparticle. A diverse team of experts is dispatched to investigate the potentially apocalyptic threat…and figure out how to stop it before this new Andromeda Evolution annihilates all life as we know it.

From the Archives

Written while Michael Crichton was still in medical school, The Andromeda Strain caused an immediate sensation: partly because the author was still in his twenties; partly because it focused on a biological crisis when most people were thinking about nuclear crises; and partly because of the cool, non-fiction tone it adopted to tell its story. Many people wrote to ask if the book was true. The author became a celebrity.

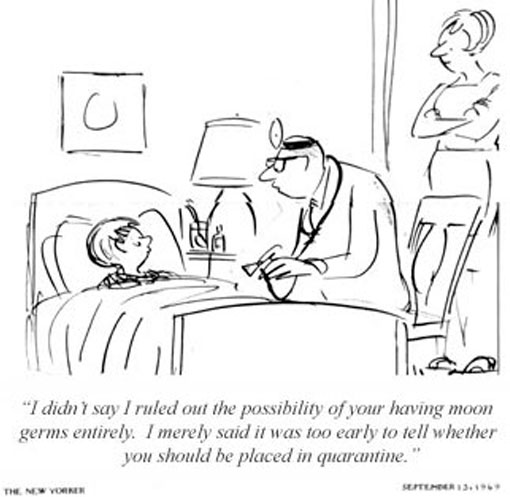

The novel was published just weeks before the first lunar landing and for weeks there had been concern about whether the astronauts would bring back germs from the moon. NASA’s decontamination procedures seemed oddly to mirror those in the novel, and the young author appeared on television with Walter Cronkite the night of the lunar landing. The “germs from outer space” theme was treated lightly in some quarters.

Readers in the 1960s were fascinated by the technologies discussed in the book: remote surveillance; voice activated systems; computer imaging and diagnosis; handprint identification; hazmat suits, and biosafety procedures. This was very new to readers forty years ago.

Politics and BioWar

Politics, not science, was the reason the novel was viewed as a radical left-wing, anti-American, anti-militarist work. In the US, many critics drew the opposite conclusion: its Harvard-trained author was located firmly in the establishment, and many questioned whether Michael Crichton was acting unethically, by giving the military new ideas for biological weapons. (He wasn’t.)

Thus the pattern of political controversy that would follow much of Michael Crichton’s work was established very early.

But as Michael Crichton repeatedly explained, his purpose in writing had nothing to do with politics. His point concerned science. He intended to give a fictional example of a particular kind of scientific crisis-one that, once begun, can’t be satisfactorily ended. He argued that we need to understand there is a category of technological error-an oil spill is a good example-that is best dealt with by never letting it happen in the first place. Once it starts, it will run its course and little can be done to alter or modify it. These crises, he said, occur irrespective of the particular people involved, and their particular personalities. We tend to think that crises can be resolved by good leaders, but technological crises often cannot be influenced at all. A skilled leader-one that is more technically trained, or smarter, or quicker-acting-is unlikely to be able to deal with an oil spill better than anyone else. Major technological crises proceed with complete indifference to personalities. The book tried to make that point, too.

In His Own Words

In the early 1990s, interviewers began calling me “the father of the techno-thriller.” Nobody had ever had before. Finally I began asking the interviewers, “Why do you call me that?” They said, “Because Tom Clancy says you are the father of the techno-thriller.” So I called Tom up and said, “Listen, thank you, but I’m not the father of the techno-thriller.” He said, “Yes you are.” I said, “No, I’m not, before me there were thrillers like Failsafe and Seven Days In May and The Manchurian Candidate that were techno-thrillers.” He said, “No, those are all political. You’re the father of the techno-thriller.” And there it ended.

“Father of the Techno-Thriller”

In the 1980s, Tom Clancy began to refer to Michael Crichton as the father of the techno-thriller, and the term has stuck. Michael Crichton points to a strong tradition of technical thrillers that preceded his own writing: Peter George’s Red Alert (1958), Richard Condon’s The Manchurian Candidate (1959); Burdick and Wheeler’s Fail-Safe (1962), and Knebel and Bailey’s Seven Days in May (1962), all of which became movies.

Subsequent History

In the years after the novel’s release, any newly-discovered biological agent tended to be referred to as an Andromeda Strain. The term became synonymous with any potential pandemic: marburg, ebola, bird flu, and so on. In the early years of AIDS the virus was often referred to as an Andromeda Strain, and the novel was erroneously cited as predicting such new strains.

Michael Crichton eventually wrote about it in an essay about AIDS:

Someone wants me to speak at a medical convention on AIDS: the modern day Andromeda Strain. I get invitations like this every few weeks.

“No,” I say to the caller. “I won’t do that.”

“You’d be performing a public service…”

“No I wouldn’t. Because AIDS is not the Andromeda Strain. And people don’t need to be made more fearful right now.”

For the last year, the rumors have been flying. The AIDS virus was manufactured by the CIA. (It unquestionably wasn’t.) Mosquitoes can infect you with the AIDS virus. (Unproven, and unlikely.) Doctors who care for AIDS patients are getting the disease (none has, except those in a known risk group.) One hundred percent of the population of Zaire now has AIDS. (Wrong.)

So I am not going to add to the rumors in any way. I refused to speak.

However, the novel stands as the first popular work to alert the public to the growing power of biological science, and to hint that biology would eventually replace physics and nuclear technology as a source of public concern and interest. Thus, the hazmat-suited figures that were so exotic in the movie forty years ago are now all-too-common.

The Making of The Andromeda Strain movie

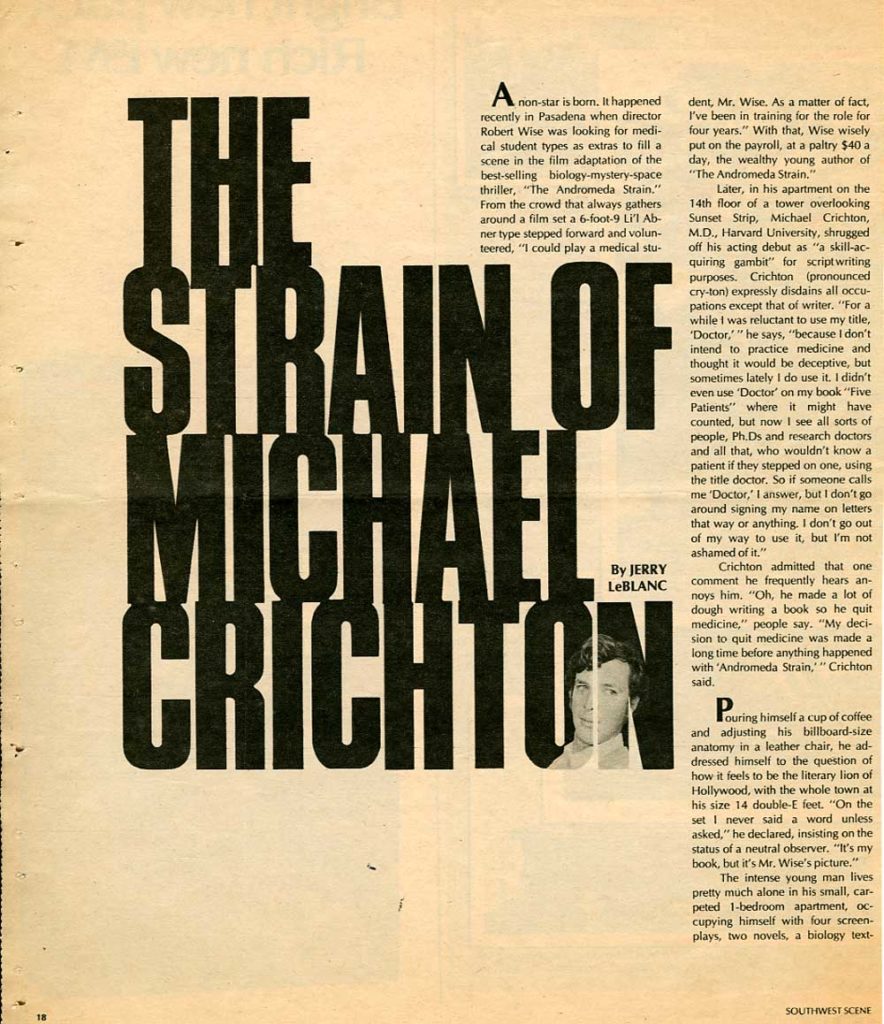

In this excerpt, from “The Strain of Michael Crichton” which appeared in the May 7, 1971 issue of Southwest Scene, the article’s author Jerry LeBlanc relates the story of how Michael Crichton came to have a cameo in the movie adaptation of his best-selling novel:

“A non-star is born. It happened recently in Pasadena when director Robert Wise was looking for medical student types as extras to fill a scene in the film adaptation of the best-selling biology-mystery-space thriller, “The Andromeda Strain.” From the crowd that always gathers around a film set a 6-foot-9 Li’l Abner type stepped forward and volunteered,” I could play a medical student, Mr. Wise. As a matter of fact, I’ve been training for the role for four years,” With that, Wise wisely put on the payroll, at a paltry $40 a day, the wealthy young author of The Andromeda Strain.

In His Own Words

[On whether The Andromeda Strain could ever happen] I doubt it very much. I wrote it because I thought it was an interesting story, and also because it illustrated a technological problem—once something goes wrong, you have trouble ever getting it right again. In other words, if there’s an oil slick on the ocean, adding detergents produces more problems, and compensating for the detergents produces another generation of problems… it was this idea that I was after. The best way to prevent problems is to prevent, not try to correct them.

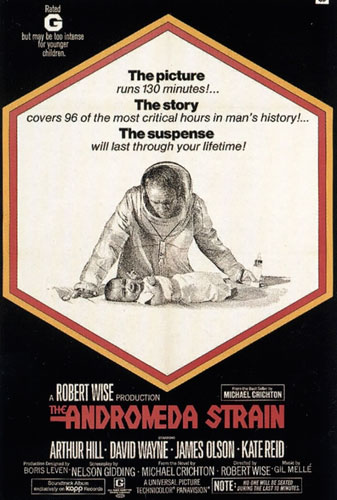

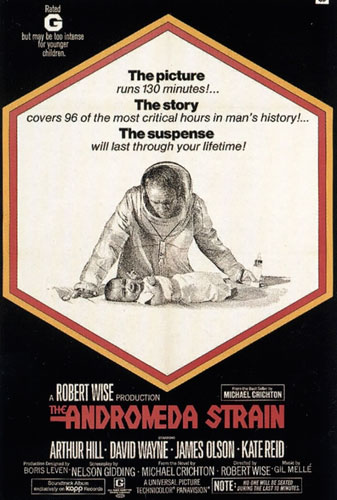

The Andromeda Strain (Movie)

| Release Date: | March 12, 1971 |

| Running Time: | 2 HRS 10 MIN |

| MPAA: | PG13 |

| Director: | Robert Wise |

| Screenwriter: | Nelson Gidding |

| Based on the Novel By: | Michael Crichton |

| Studio: | Universal Pictures |

| Starring: | Arthur Hill, James Olson, Kate Reid, David Wayne, Paula Kelly, George Mitchell |

In His Own Words

Bob Wise was really very nice about letting people watch and learn from what he was doing. I was just the writer of the book, hanging around the set – which was a totally non-existent function. But he had, as I recall, an AFI intern and a Director’s Guild trainee on the project, mostly just watching. I had never seen any kind of a film made before, except during brief visits to stages for a few minutes. Bob was the first director I’d ever had a chance to observe at work and, in an awful lot of ways, he’s the model I’ve retained. Bob dealt with all of the problems very smoothly. His particular style of directing is very relaxed, very easygoing, very personal and very well-organized, without a lot of histrionics and temper flares. That impressed me a lot and I’ve tried very hard to be that way, too.

Book Covers