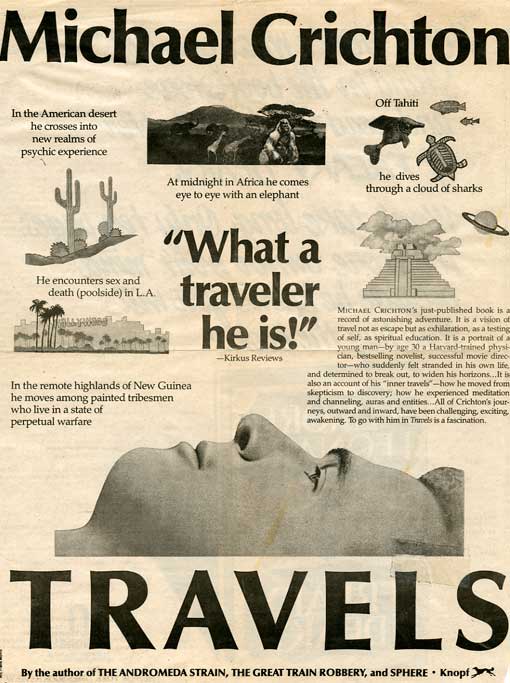

Travels

In His Own Words

I first considered writing a book of travel experiences in the summer of 1981, while I was sitting, thoroughly bored, on a beach in the Seychelles, waiting for a flight to Dar-es-Salaam, Tanzania. But I did not actually get around to working on it until 1986.

When I start a new book, I never know how it will go. Some books flow rather easily, and seem to happen naturally, almost effortlessly. I just show up at the word processor and the pages come out. Other books are a constant struggle and each day feels like a battle, each sentence and paragraph hard won. These difficult books usually require extensive revision, and sometimes must be entirely rewritten three or four times.

This difficulty of writing seems unrelated to anything I can identify: my own preparation, my life at the time, the complexity of the planned book, and so on. Some books are easy, some are not. All I can do is begin one, and see how it goes.

Because I had never written an autobiographical book before, I regarded Travels with some trepidation. In truth I had been postponing it for some time; one of my New Year’s resolutions for 1986 was to get started on it, and I began the book on January 5 of that year, before I lost my nerve.

I soon realized this writing experience would be like no other I’d ever had. Ordinarily I work in brief, intense bursts, completing a manuscript draft in four to eight weeks, then setting it aside for many months, before doing another intense revision. After several such revisions, the book is either ready for publication, or so clearly flawed that I abandon it forever. But Travels followed a different pattern entirely. The first draft took six months, longer than any I had written before. The work advanced slowly but steadily, and I found it unusually rewarding. I finished each chapter with a sense of relief and even elation, as if I had been freed from some burden I did not know I was carrying. I felt invigorated, and emboldened to attempt more difficult episodes. So as I went along, Travels became more explicit and more personal than I had first imagined it would be.

Now, one of the odd problems of writing is that you cannot trust your subjective sensations about how the work is going while you are doing it. Of course, you have feelings about the work, but those feelings are constantly shifting: I am often wildly delighted and deeply discouraged in the space of a single day. In any case, over the years I have learned that nearly all the strong feelings I have at the time of writing are likely to be wrong. Because the sections that I like best—the sections that make me laugh as I write them, those paragraphs that make me pat myself on the back as I read them over—are the sections that seem cute and excessive a few months later, when I cut them, wondering why I ever thought they were any good. And conversely, the passages I dislike at the time I write them, the paragraphs that seem clunky or obscure, often look just fine at a later date.

So the elation I felt while writing Travels caused me to be suspicious about my first draft during the spring of 1986. I was pleased when, in early 1987, I picked up the manuscript to begin revisions and found I still liked most of it. There were many chapters I disliked (they are gone now); many others that I found unclear (they are, I trust, clearer now); and many that I found too long (they are shorter.) One chapter was removed for legal reasons, and many names were changed for legal reasons. But through all the changes and the subsequent drafts, I found I still liked this book. I hope you do, too.

Synopsis

“Often I feel I go to some distant region of the world to be reminded of who I really am.”

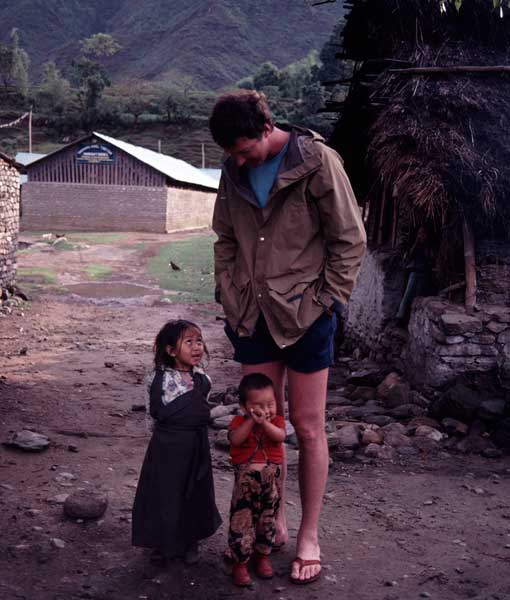

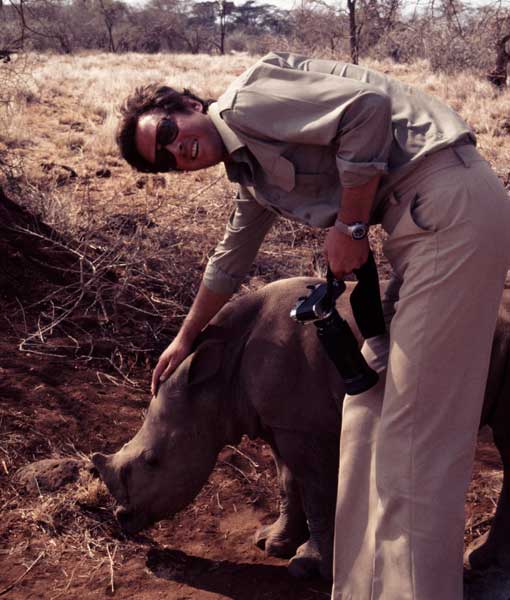

When Michael Crichton — a Harvard-trained physician, bestselling novelist, and successful movie director — began to feel isolated in his own life, he decided to widen his horizons. He tracked wild animals in the jungles of Rwanda. He climbed Kilimanjaro and Mayan pyramids. He trekked across a landslide in Pakistan. He swam amid sharks in Tahiti.

Fueled by a powerful curiosity and the need to see, feel, and hear firsthand and close-up, Michael Crichton has experienced adventures as compelling as those he created in his books and films. These adventures — both physical and spiritual — are recorded here in Travels, Crichton’s most astonishing and personal work.

Passage 1

In Travels, Michael Crichton relates his experience at a Spoon Bending Party. We excerpt a portion of his story here.

I looked down. My spoon had begun to bend. I hadn’t even realized. The metal was completely pliable, like soft plastic. It wasn’t particularly hot, either, just slightly warm. I easily bend the bowl of the spoon in half, using only my fingertips. This didn’t require any pressure at all, just guiding with my fingertips.

I put the bent spoon aside and tried a fork. After a few moments of rubbing, the fork twisted like a pretzel. It was easy. I bent several more spoons and forks.

Then I got bored. I didn’t do any more spoon bending. I went and got coffee and a cookie. I was now far more interested in what kind of cookies they had then anything else.

Of course, spoon bending has been the focus of long-standing controversy. Uri Gellar, an Israeli magician, who claims psychic powers, often bends spoons, but other magicians, such a James Randi, claim that spoon bending isn’t a psychic phenomenon at all, just a trick.

But I had bent a spoon, and I knew it wasn’t a trick. I looked around the room and saw little children, eight or nine years old, bending large metal bars. They weren’t trying to trick anybody. They were just little kids having a good time. Staying up past their bedtimes on a Friday night, going along with the adults, doing this silly bending stuff.

So much for the controversy between magicians, I thought. Because spoon bending obviously must have some ordinary explanation, since a hundred people from all walks of life we’re doing it. And it was hard to feel any sort of mystery: you just rub the spoon for a while and pretty soon it gets soft, and it bends. And that’s that.

The only thing I noticed is that spoon bending seemed to require a focused inattention. You had to try to get it to bend, and then you had to forget about it. Maybe talk to someone else while you rubbed the spoon. Or look around the room. Change your attention. That’s when it was likely to bend. If you kept watching the spoon, worrying over it, it was less likely to bend. This inattention took learning, but you could easily do it. It was comparable in difficulty to, say, learning to count off exactly five seconds in your head. You practiced a few times, and then you could do it.

Why do spoons bend? Jack Houck had theories, but I had long since decided to concentrate on the phenomena, and not worry about the theories. So I don’t know why spoons bend, but it seemed clear that almost anyone could do it.

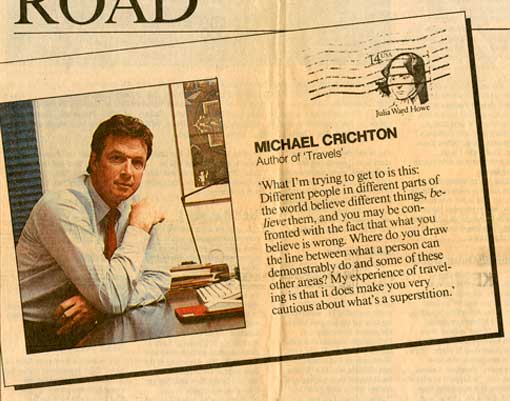

In His Own Words

Of all the things I wrote about, spoon bending seems to stick in the rationalist throat. It just bugs people. I don’t know why.

I don’t know why spoon-bending occurs. I have no explanation. I can’t describe it any better than I did in the book. But I have no doubt that it occurs. More than seeing adults bend spoons (they might be using brute force to do it, although if you believe that I suggest you try, with your bare hands, to bend a decent-weight spoon from the tip of the bowl back to the handle. I think you’d need a vise.)

But to see a little kid of 8 or 10 running around with a thick bar of aluminum that he has bent-not a lot, but enough so that if you roll it on a table, it doesn’t roll flat-is to realize that whatever is going on, it’s not brute force. I think that spoon bending is not “psychic” or bugga-bugga. It’s something pretty normal, but we don’t understand it. So we deny its existence.

Passage 2

Passage 3

In His Own Words

The new book is nonfiction. It’s an autobiographical book and it began as a series of travel pieces. I’ve done a lot of traveling in the last twenty years. Originally, my idea was never to write about it. My thought was that I wanted to do something that I just did for myself and wasn’t work-related; it wasn’t supposed to amount to anything; wasn’t supposed to turn into anything. But, as time went on, so many of the really important experiences in my life occurred on those trips that it began to seem almost evasive to me that I wasn’t writing about it. So I finally decided that I would. Once I was writing an auto-biographical book—which certainly I never thought I’d do—I began to think about some medical stories that I’d always promised myself that I’d write, although not until enough time had gone by that they were pretty ancient history. To my amazement, enough time has gone by. It’s more than fifteen years since I went to medical school, so I’ve put those in there too.

In His Own Words

I had never written anything autobiographical, and traveling was an important part of my life. I felt as if I was kind of keeping a secret by never writing about it. Anyway, I felt unburdened in some way when it was finished.

In His Own Words

Michael Crichton in the San Diego Union

“To Crichton, quest is for a fresh outlook”, June 2, 1988

Book Covers