Five Patients

In His Own Words

Medicine had become not a changed profession but a perpetually changing one. There is no longer a sense that one can make a few adjustments and then return to a steady state, for the system will never be stable again. There is nothing permanent except for change itself.

From this standpoint, the experiences of five patients in a university teaching hospital are most interesting. It should be stated at once that there is nothing typical about either the patients described here or the hospital in which they were treated. Rather, they are presented because their experiences are indicative of some of the ways medicine is now changing.

These five patients were selected from a larger group of twenty-three, all admitted during the first seven months of 1969. In talking to these patients and their families, I identified myself as a fourth-year medical student writing a book about the hospital. As they are presented here, each patient’s name and other identifying characteristics have been changed.

I chose these five from the larger group because I thought their experiences were in some way particularly interesting or relevant. Accordingly, this is a highly selective and personal book, based on the idiosyncratic observation of one medical student wandering around a large institution, sticking his nose into this room or that, talking to some people and watching others and trying to decide what, if anything, it all means.

Synopsis

In this incisive, detailed survey of five patients, famous thriller author and doctor Michael Crichton explores the dramatic workings of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston’s oldest and most prestigious.

This readable account covers not only the history of the hospital’s place in society, but also the actual minute-to-minute functions of Mass General, where health professionals wage their daily battle against disease and death. Crichton’s insightful look at the changes in medicine and surgery caused by technological strides of recent years makes for amazing reading.

Passage 1

Until his admission, John O’Connor, a fifty-year-old railroad dispatcher from Charlestown, was in perfect health. He had never been sick a day in his life.

On the morning of his admission, he awoke early, complaining of vague abdominal pain. He vomited once, bringing up clear material, and had some diarrhea. He went to see his family doctor, who said that he had no fever and his white cell count was normal. He told Mr. O’Connor that it was probably gastroenteritis, and advised him to rest and take paregoric to settle his stomach.

In the afternoon, Mr. O’Connor began to feel warm. He then had two shaking chills. His wife suggested he call his doctor once again, but when Mr. O’Connor went to the phone, he collapsed. At 5 pm his wife brought him to the MGH emergency ward, where he was noted to have a temperature of 108 F and a white count of 37,000 (normal count: 5,000 – 10,000.)

Passage 2

Three inches above the left wrist the forearm had been mashed. Bones stuck out at all angles; reddish areas of muscle with silver fascial coats were exposed in many places. The entire arm about the injury was badly swollen, but the hand was still normal size, although it looked shrunken and atrophic in comparison. The color of the hand was deep blue-gray.

Carefully, Appel picked up the hand, which flopped loosely at the wrist. He checked pulses and found none below the elbow. He touched the fingers of the hand with a pin and asked if Luchesi could feel it; results were confusing, but there appeared to be some loss of sensation. He asked if the patient could move any of his fingers; he could not.

Meanwhile, the orthopedic resident, Dr. Robert Hussey, arrived and examined the hand. He concluded that both bones in the forearm, the radius and ulna, were broken and suggested the hand be elevated; he proceeded to do this.

Outside the door to the room, one of the admitting men stopped Appel. “Are you going to take it, or try to keep it?”

“Hell, we’re going to keep it,” Appel said. “That’s a good hand.”

Passage 3

“You’ll be speaking with Dr. Murphy,” the secretary said.

A nurse then came into the room and motioned Mrs. Thompson to take a seat. Mrs. Thompson looked uncertainly at all the equipment. On the screen, Dr. Raymond Murphy was looking down at some papers on his desk.

The nurse said: “Dr. Murphy.”

Dr. Murphy looked up. The television camera beneath the TV screen made a grinding noise, and pivoted around to train on the nurse.

“Yes?”

“This is Mrs. Thompson from Los Angeles. She is fifty-six-years old, and she has a chest pain. Her blood pressure is 120/80, her pulse is 78, and her temperature is 101.4.

Dr. Murphy nodded. “How do you do, Mrs. Thompson.”

Mrs. Thompson was slightly flustered. She turned to the nurse. “What do I do?”

“Just talk to him. He can see you through that camera there, and hear you through that microphone.” She pointed to the microphone suspended from the ceiling.”

“But where is he?”

“I’m at the Massachusetts General Hospital,” Dr. Murphy said.

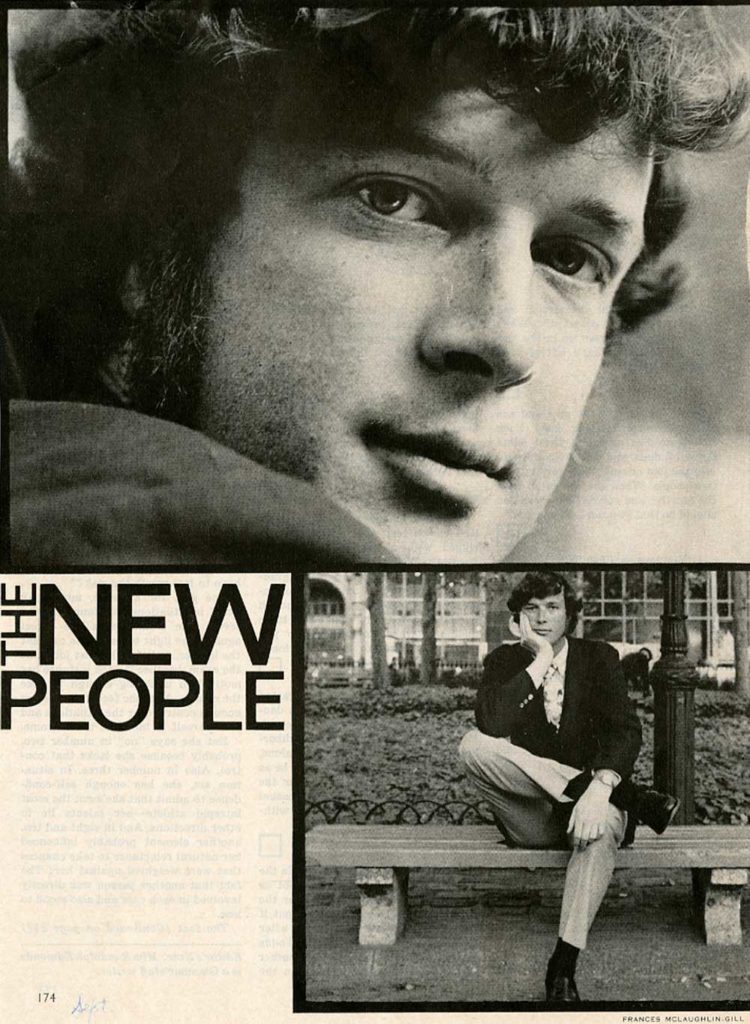

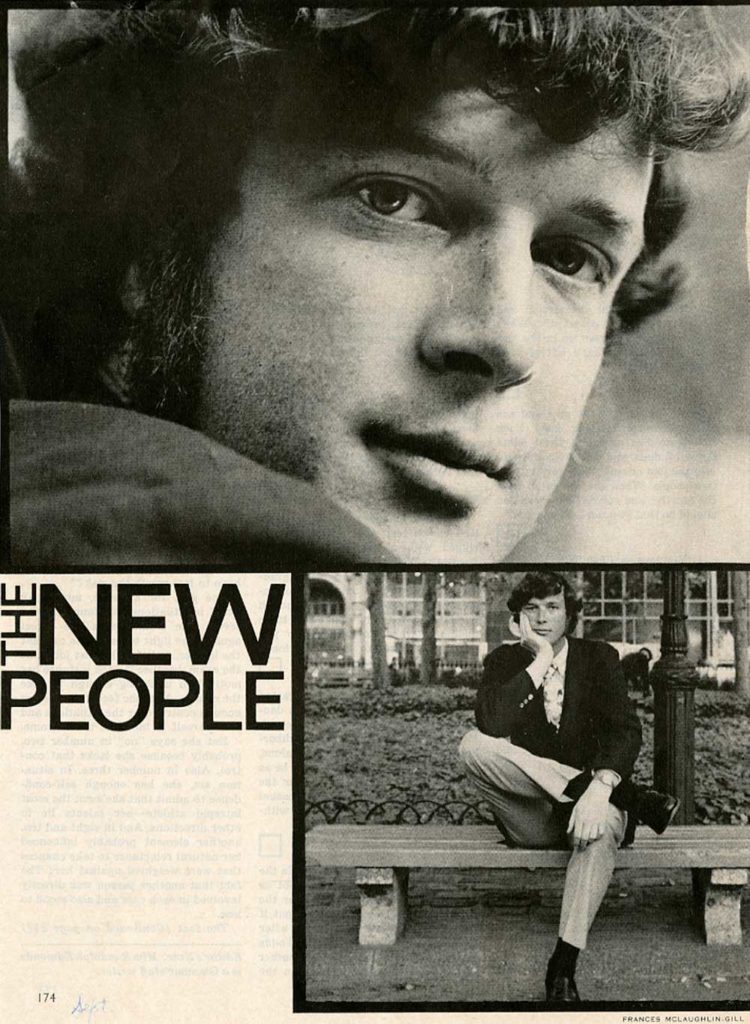

From the Archives

A September 1970 issue of Glamour magazine insightfully called Michael Crichton one of “The New People” to watch in popular culture in the 1970’s.

“Michael Crichton, still in his twenties, is a rare hybrid in our culture — a scientist and artist, crossbred between Harvard Medical School and the Book-of-the-Month Club/Hollywood movie exchange. He is the second in Glamour’s series of New People whose thinking and feeling may influence the ’70’s.”

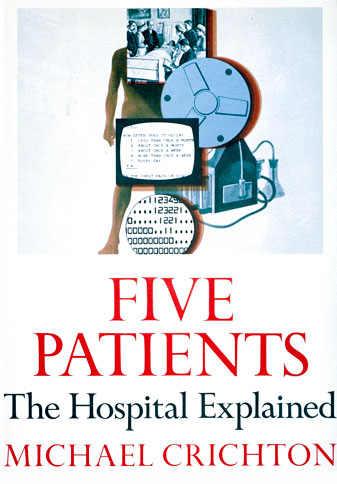

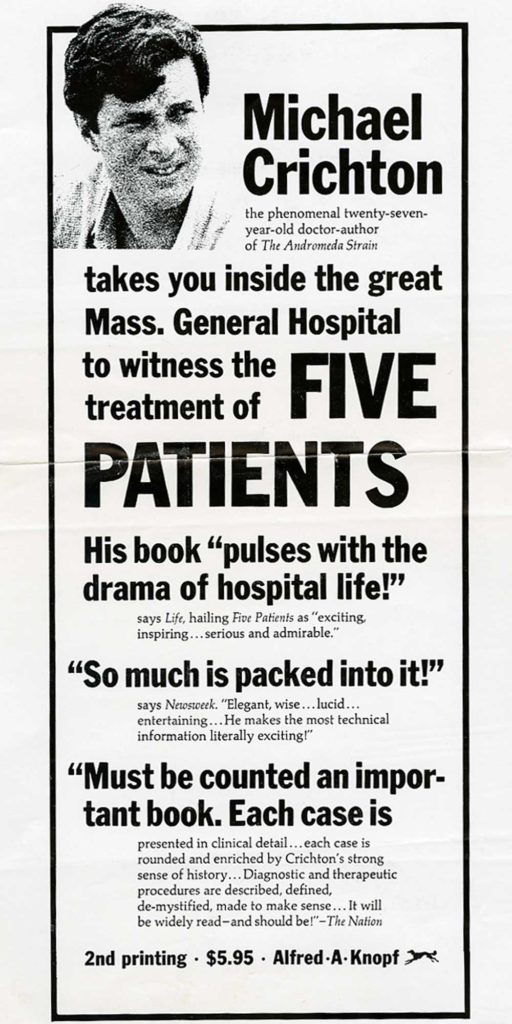

Five Patients Promotional Material

Book Covers