Congo

In His Own Words

I had always admired the H. Rider Haggard adventure story, “King Solomon’s Mines,” and I wanted to write a similar sort of Victorian adventure, set in the 20th century. I was also interested in the experimental attempts to teach apes to use language, and the implications of this research for animal rights, which in the late 1970s was a very obscure topic.

When the book was published, most reviewers found the character of Amy, the sign-language-using gorilla, too incredible to believe. This despite the fact that I had modeled Amy on a real signing gorilla, Koko, then at Stanford University. I considered Koko to be pretty famous. After all, she had been twice on the cover of National Geographic magazine, and once on the cover of the New York Times magazine. Koko had also been interviewed on television, where with quick hand gestures she complained about the bright lights, and told the TV interviewer to go away. But apparently, book reviewers had never heard of Koko.

To prepare for writing the book, I planned to go to Africa to see gorillas on the slopes of the Virunga volcano chain in eastern Congo. But at that time, there was a war between Tanzania and Uganda, and the eastern Congo were much too dangerous to visit. No one would take me there.

So I had to find substitutes. To experience volcanos, I went to Stromboli, off the coast of Sicily, a volcano which is continuously active. In those days you could just hike to the rim and watch the display as long as you wanted. For an experience in the rain forest, I went to Taman Negara in the jungles of Malaysia.

I never saw gorillas in the wild until two years after the book was published. Then I went to Rwanda, climbed the real volcanoes, and visited the real gorillas. This was a very powerful and emotional experience, which I wrote about in the book Travels.

Synopsis

Deep in the African rain forest, near the legendary ruins of the Lost City of Zinj, an expedition of eight American geologists is mysteriously and brutally killed in a matter of minutes.

Ten thousand miles away, Karen Ross, the Congo Project Supervisor, watches a gruesome video transmission of the aftermath: a camp destroyed, tents crushed and torn, equipment scattered in the mud alongside dead bodies — all motionless except for one moving image — a grainy, dark, man-shaped blur.

In San Francisco, primatologist Peter Elliot works with Amy, a gorilla with an extraordinary vocabulary of 620 “signs,” the most ever learned by a primate, and she likes to fingerpaint. But recently, her behavior has been erratic and her drawings match, with stunning accuracy, the brittle pages of a Portuguese print dating back to 1642 . . . a drawing of an ancient lost city. A new expedition — along with Amy — is sent into the Congo where they enter a secret world, and the only way out may be through a horrifying death …

Passage 1

Something struck him lightly in the chest. At first he thought it was an insect but, glancing down at this khaki shirt, he saw a spot of red, and a fleshy bit of red fruit rolled down his shirt to the muddy ground. The damned monkeys were throwing berries. He bent over to pick it up. And then he realized that it was not a piece of fruit at all. It was a human eyeball, crushed and slippery in his fingers, pinkish white with a shred of white optic nerve still attached at the back.

He swung around and looked over to where Misulu was sitting on the rock. Misulu was not there.

Kruger moved across the campsite. Overhead, the colubus monkeys fell silent. He heard his boots squish in the mud as he moved past the tents of sleeping men. And then he heard the wheezing sound again. It was an odd, soft sound, carried on the swirling mourning mist. Kruger wondered if he had been mistaken, if it really was a leopard.

And he saw Misulu. Misulu lay on his back, in a kind of halo of blood. His skull had been crushed from the sides, the facial bones shattered, the face narrowed and elongated, the mouth open in an obscene yawn, the one remaining eye wide and bulging. The other eye had exploded outward with the force of impact.

Kruger felt his heart pounding as he bent to examine the body. He wondered what could have caused such an injury. And then he heard the soft wheezing sound again, and this time he felt quite sure it was not a leopard. Then the colubus monkeys began their shrieking, and Kruger lept to his feet and screamed.

Passage 2

“The computer’s picking the fastest route. You see it just identified a timeline that will get us on-site in six days eighteen hours and fifty-one minutes. Now it’s trying to beat that time.”

Elliot had to smile. The idea of a computer predicting to the minute when they would reach their Congo location seemed ludicrous to him. But Ross was totally serious.

As they watched, the computer clock shifted to 5 days 22 hours 24 minutes.

“Better,” Ross said, nodding. “But still not very good.” She pressed another key and the lines shifted, stretching like rubber bands over the African continent. “This is the consortium route,” she said, “based on our assumptions about the expedition. They’re going in big – thirty or more people, a full-scale undertaking. And they don’t know the exact location of the city; at least, we don’t think they know. But they have a substantial start on us, at least twelve hours, since their aircraft is already forming up in Nairobi.”

The clock registered total elapsed time: 5 days 09 hours 19 minutes. Then she pressed a button marked DATE and it shifted to 06 21 0814. “According to this, the consortium will reach the Congo site a little after eight o’clock in the morning on June 21.”

Passage 3

There is no doubt that Peter Elliot felt a personal threat in these developments, although not a threat to his safety. “I simply couldn’t accept it,” he said later. “I knew my field, and I simply couldn’t accept the idea of some unknown, radically violent behavior displayed by gorillas in the wild. And in any case, it didn’t make sense. Gorillas making stone paddles that they used to crush human skulls? It was impossible.”

After examining the body, Elliot went to the stream to wash the blood from his hands. Once alone, away from the others, he found himself staring into the clear running water and considering the possibility that he might be wrong. Certainly primate researchers had a long history of misjudging their subjects.

Elliot himself had helped eradicate one of the most famous misconceptions – the brutish stupidity of the gorilla. In their first descriptions, Savage and Wyman had written, “This animal exhibits a degree of intelligence inferior to that of the chimpanzee; this might be expected from its wider departure from the organization of the human subject.” Later observers saw the gorilla as “savage, morose, and brutal.” But now there was abundant evidence from field and laboratory studies that the gorilla was in many ways brighter than the chimpanzee.

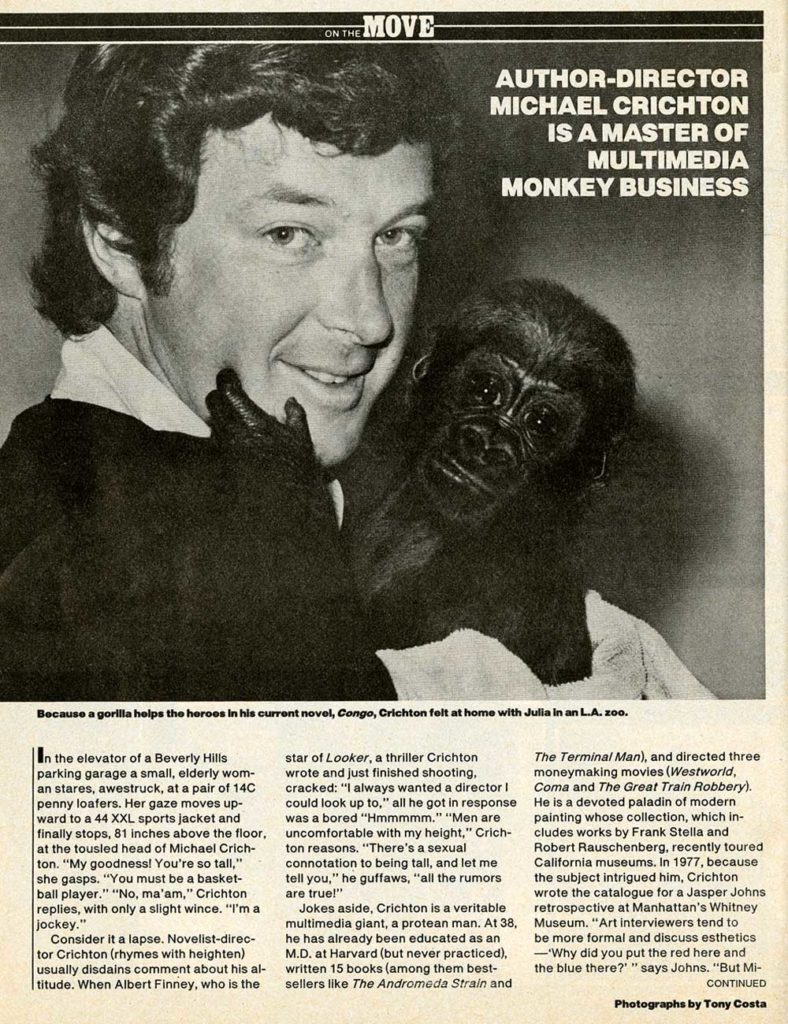

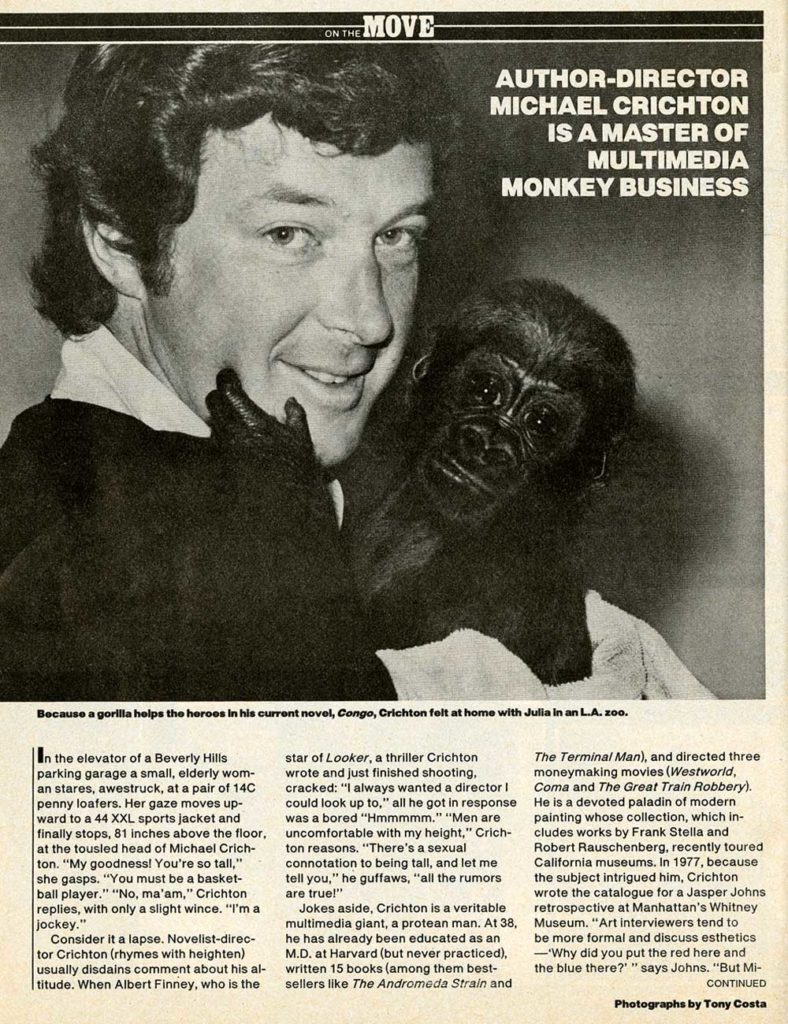

From the Archives

People magazine featured Michael Crichton in the February 16, 1981 issue in an articled titled “Author-Director Michael Crichton Is a Master of Multimedia Monkey Business” and written by Andrea Chambers. Michael Crichton talks about writing, directing and his latest novel, Congo. Here is an excerpt:

“Crichton cheerfully admits that Congo owes more than its exotic locale to Sir Henry Rider Haggard’s classic “King Solomon’s Mines”. “All the books I’ve written play with preexisting literary forms,” Crichton says. A model for The Andromeda Strain was H.G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds. The Terminal Man was based on Frankenstein’s monster. Crichton’s 1976 novel Eaters of the Dead was inspired by Beowulf. “The challenge is in revitalizing the old forms,” he explains.

Crichton taps out his books on an Olivetti word processor (price: $13,500) and bombards readers with high-density scientific data and jargon, only some of which is real. “I did check on the rapids in the Congo,” he says. “They exist, but not where I put them.” His impressive description of a cannibal tribe is similarly fabricated. “It amused me to make a complete ethnography of a nonexistent tribe,” he notes. “I like to make up something to seem real.””

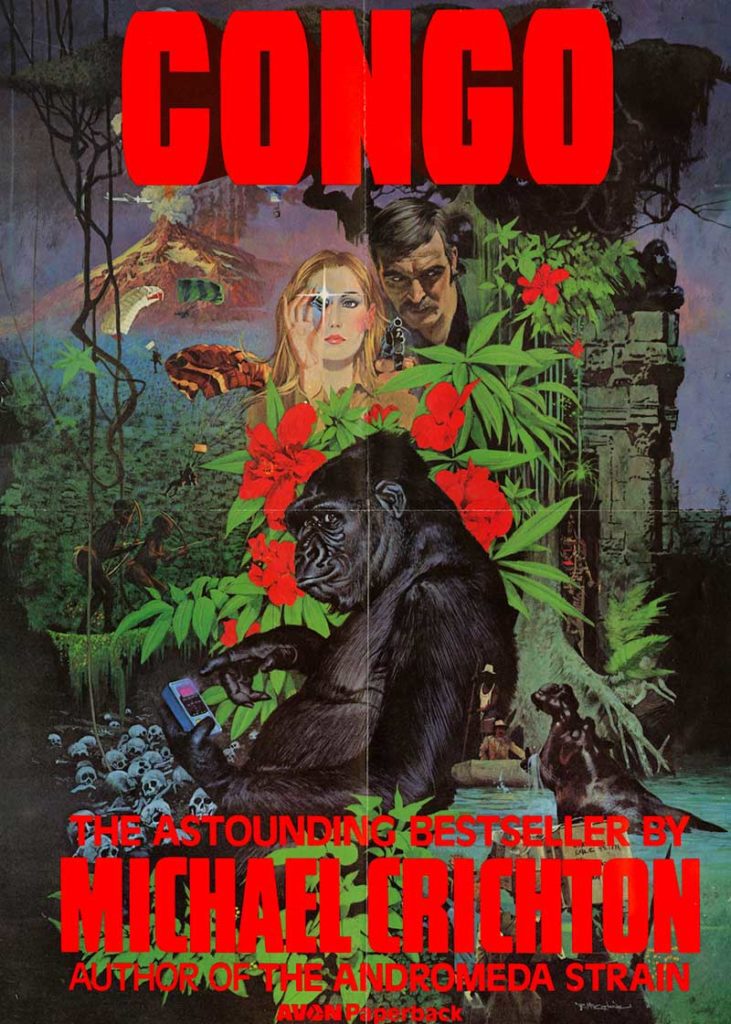

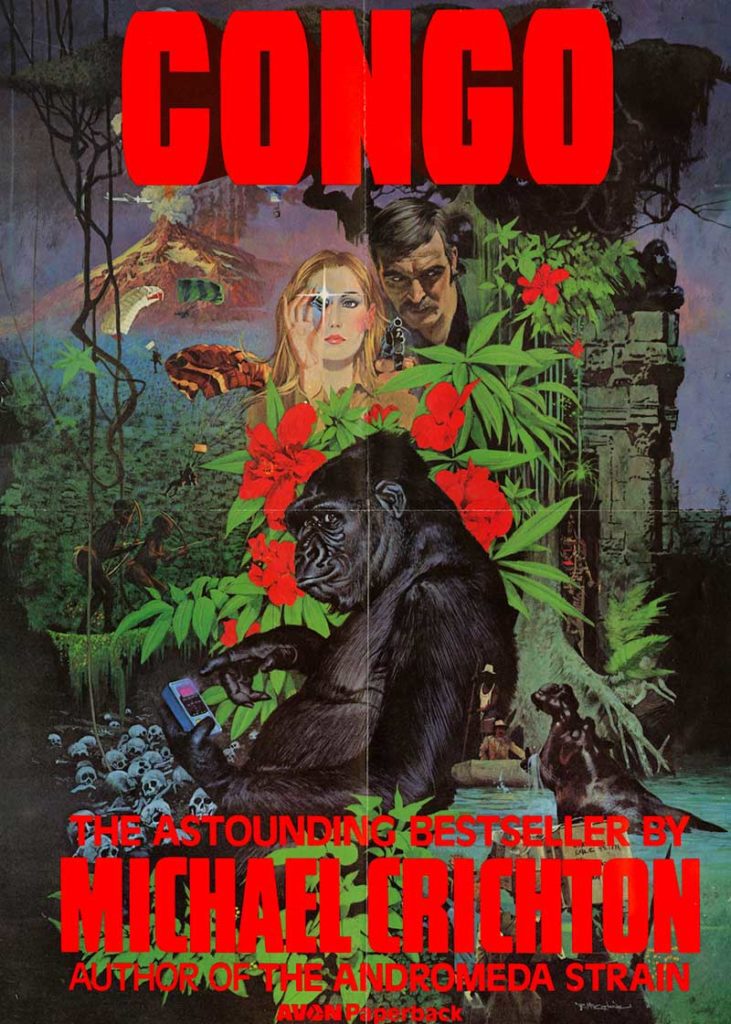

Promotional poster for the paperback release of Congo created by renowned artist and illustrator Robert McGinnis.

Congo (Movie)

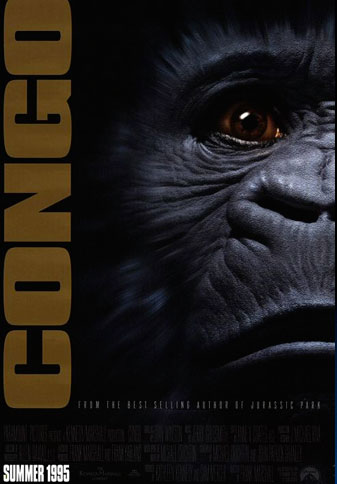

| Release Date: | JUNE 9, 1995 |

| Running Time: | 1 HR. 49 MIN. |

| MPAA: | PG13 |

| Director: | Frank Marshall |

| Screenwriter: | John Patrick Shanley |

| Based on the Novel by: | Michael Crichton |

| Studio: | Paramount Pictures |

| Starring: | Laura Linney, Dylan Walsh, Ernie Hudson, Tim Curry, Joe Don Baker |

Congo was one of the Top 20 movies of 1995

Book Covers