Spotlight on Michael Crichton's Medical Career

Medical school had a profound influence on Michael Crichton’s understanding of science, the medical industry and life in general. These early experiences and the knowledge gained while in attendance informed his sensibilities and interests for his entire career. As a backdrop for his storytelling, Michael Crichton continuously returned to his time in medical school to explore the political and moral issues posed by modern medicine, technology and scientific breakthroughs.

In His Own Words

When I was in college, I wanted to be a writer. But then I read that only two hundred writers in America support themselves writing. I thought, “That’s an awfully small group.” I didn’t want to be a part-time writer with a day job—that didn’t interest me. I either had to be one of those two hundred people or forget it. So I decided to become a doctor. I was attracted to medicine partly because I thought I would be doing useful work, helping people—I would never have to wonder if the work was worthwhile. But many working physicians are not convinced at all. They have all kinds of doubts, which troubled me. I also found that I was at odds with the thrust of the profession at the time, which was highly scientific medicine: the physician as technician and the patient as biological machine that was broken. I didn’t find it appealing to work in that kind of setting.

A medical student always is in the position of not knowing how to do something. Medicine also got you into the frame of mind of dealing with very high-pressure situations, dealing with complex factors, emergencies. You often had to act and make fast decisions. Something is always going wrong in a movie, and that kind of experience is invaluable in salvaging a situation. Directing is really hard work.

HARVARD MEDICAL SCHOOL

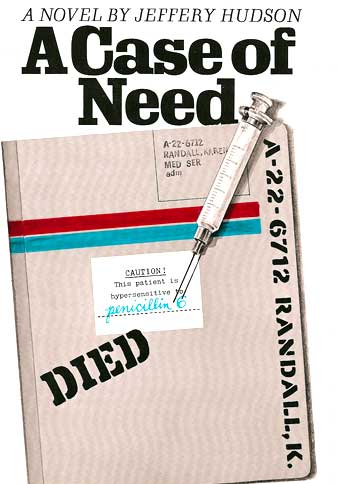

Michael Crichton graduated summa cum laude from Harvard College in 1964 and received his MD from Harvard Medical School in 1969. While at Harvard Medical School, Michael Crichton wrote book reviews for the Harvard Crimson and novels under the pseudonyms John Lange and Jeffery Hudson, among them A Case of Need, which won the Edgar Award for Best Mystery in 1969.

In contrast to the carefully researched techno-thrillers that ultimately brought him to fame, the Lange and Hudson books are high-octane novels of suspense and action. Written with remarkable speed and gusto, these novels provided Crichton with both the means to study at Harvard Medical School and the freedom to remain anonymous in case his writing career ended before he obtained his medical degree. The Andromeda Strain, his first bestseller, was published under his own name. The movie rights for The Andromeda Strain were bought in February of his senior year at Harvard Medical School.

Michael Crichton never practiced medicine, opting instead to concentrate on his writing and filmmaking career.

In His Own Words

The only other doctor I know of who’s done the same thing [left medicine to become a filmmaker], Jonathon Miller, has said something which I think is true — namely, that being a doctor is good preparation for this, because it teaches you to deal with the kind of life that you will inevitably have. It teaches you to work well when you haven’t had enough sleep. It teaches you to work well when you’re on your feet a lot. It teaches you to work well with technical problems and it teaches you to make decisions and then live by them. I think it also has advantages in working with actors, because one of the things a doctor has to learn is to be able to meet a patient whom he has never seen before and rapidly assess him in terms of what kind of person he is, and not merely whether he’s perforated his ulcer. You’ve got to be able to analyze just what kind of person you’re dealing with. Are you dealing with someone who will take medicines if you prescribe them, or is he the kind of person who says he will, but won’t? Those decisions get to be very important and training to be a doctor builds up that capability for assessing people rapidly which is necessary when it come to working with actors. I’m not quite sure just how the transition from medicine to movies came about, except, as I’ve said, that I think I’ve always wanted to make movies. When I got into medicine, I was disappointed in a lot of ways, so it was a pull from one direction and a push from the other.

NOVELS MICHAEL CRICHTON WROTE WHILE ATTENDING MEDICAL SCHOOL

In His Own Words

I am often asked my favorite [of his novels written under a pseudonym.] It is A Case of Need. The most difficult was Five Patients, because it required me to summarize my experience in medical school. The most interesting writing problem was Andromeda; it was a question of how to make it believable. The most amusing was Zero Cool, where I set out to rewrite, utilizing all the elements of the original, The Maltese Falcon.

The Salk Institute for Biological Studies

Michael Crichton was also a postdoctoral fellow at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies in 1970.

In His Own Words

I was about twenty-five and I’d spent all of my life in some academic setting and now it was over. I was about to be ejected into the world and I needed a kind of halfway house, so I went to the Salk Institute in La Jolla. Salk had an idea that along with the biomedical people who were primarily staffing the place, he was going to have writers and artists in residence. So I sent him a letter and said, “I’m a writer.” He said, “Come.” So I went. It was great.

While working at The Salk Institute, Michael Crichton also spent time on the set of the first movie made from one of his books. Find our more in our The Andromeda Strain section.

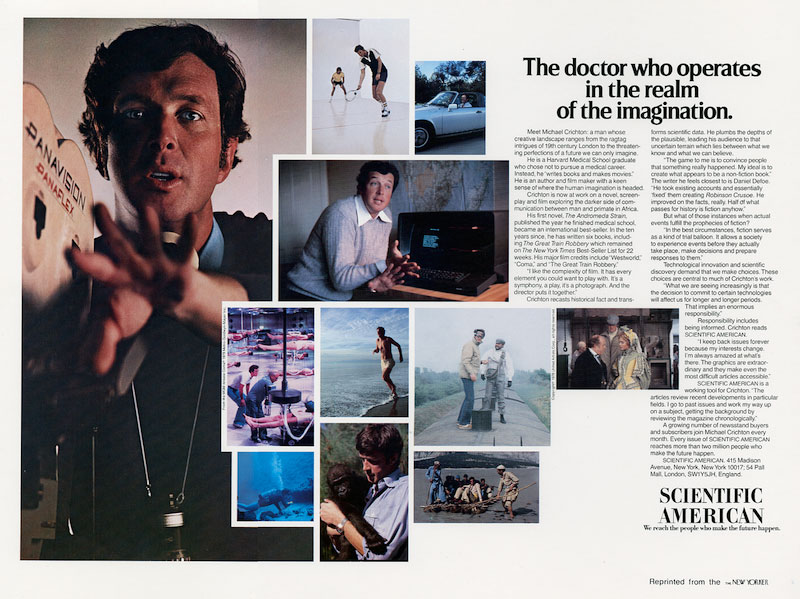

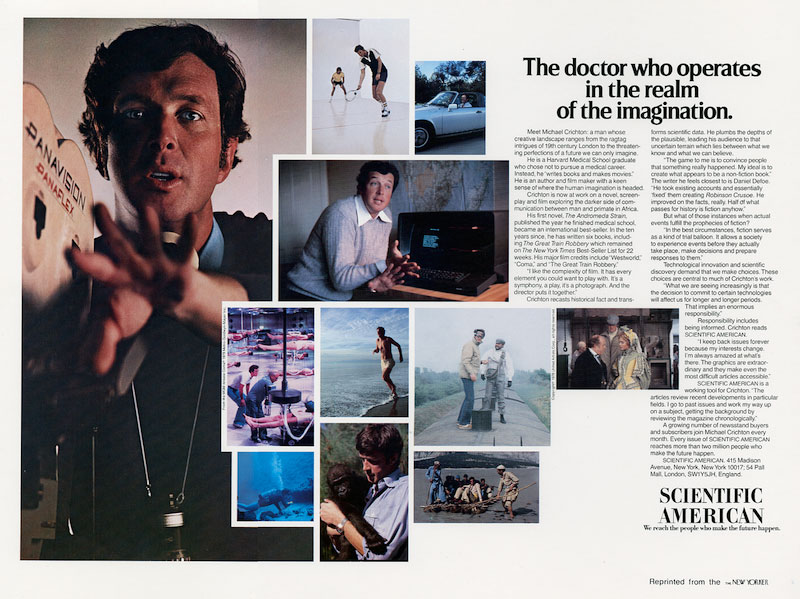

Michael Crichton – Scientific American

Michael Crichton was featured in an ad for Scientific American that appeared in the New Yorker magazine. Here is the text from that ad:

Meet Michael Crichton, a man whose creative landscape ranges from the ragtag intrigues of 19th century London to the threatening predictions of a future we can only imagine.

He is a Harvard Medical School graduate who chose not to pursue a medical career. Instead he “writes books and makes movies.” He is an author and film maker with a keen sense of where the human imagination is headed.

Crichton is now at work on a novel, screenplay and film exploring the darker side of communication between man and primate in Africa.

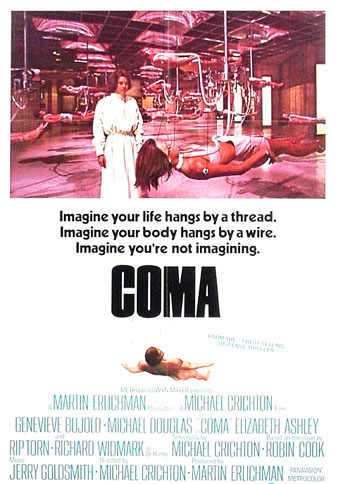

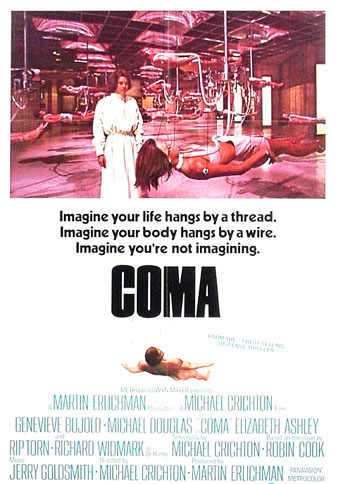

His first novel, The Andromeda Strain, published the year he finished medical school, became an international best-seller. In the ten years since, he has written six books, including The Great Train Robbery, which remained on the New York Times Best Seller List for 22 weeks. He major film credits include Westworld, Coma and The Great Train Robbery.

“I like the complexity of film. It has every element you could want to play with. It’s a symphony, a play, it’s a photograph. And the director pulls it together.”

Crichton recasts historical fact and transforms scientific data. He plumbs the depths of the plausible, leading his audience to that uncertain terrain which lies between what we know and what we can believe.

“The game to me is to convince people that something really happened. My ideal is to create what appears to be a non-fiction book.” The writer he feels closest to is Daniel Dafoe. “He took existing accounts and essentially “fixed” them creating Robinson Crusoe. He improved on the facts, really. Half of what passes for history is fiction anyhow.”

But what of these instances when actual events fulfill the prophecies of fiction?

“In the best circumstances, fiction serves as a kind of trial balloon. It allows a society to experience events before they actually take place, make decisions and prepare responses to them.”

Technological innovation and scientific discovery demand that we make choices. These choices are central to much of Crichton’s work.

“What we are seeing increasingly is that the decision to commit to certain technologies will affect us for longer and longer periods. That implies an enormous responsibility.

Responsibility include being informed. Crichton reads Scientific American.

“I keep back issues forever because my interests change. I’m always amazed at what’s there. The graphics are extraordinary and they make even the most difficult articles accessible.”

Scientific American is a working tool for Crichton. “The articles review recent developments in particular fields. I go to past issues and work my way up on a subject, getting the background by reviewing the magazine chronologically.

A growing number of newsstand buyers are subscribers and join Michael Crichton every month. Every issue of Scientific American reaches more than two million people who make the future happen.

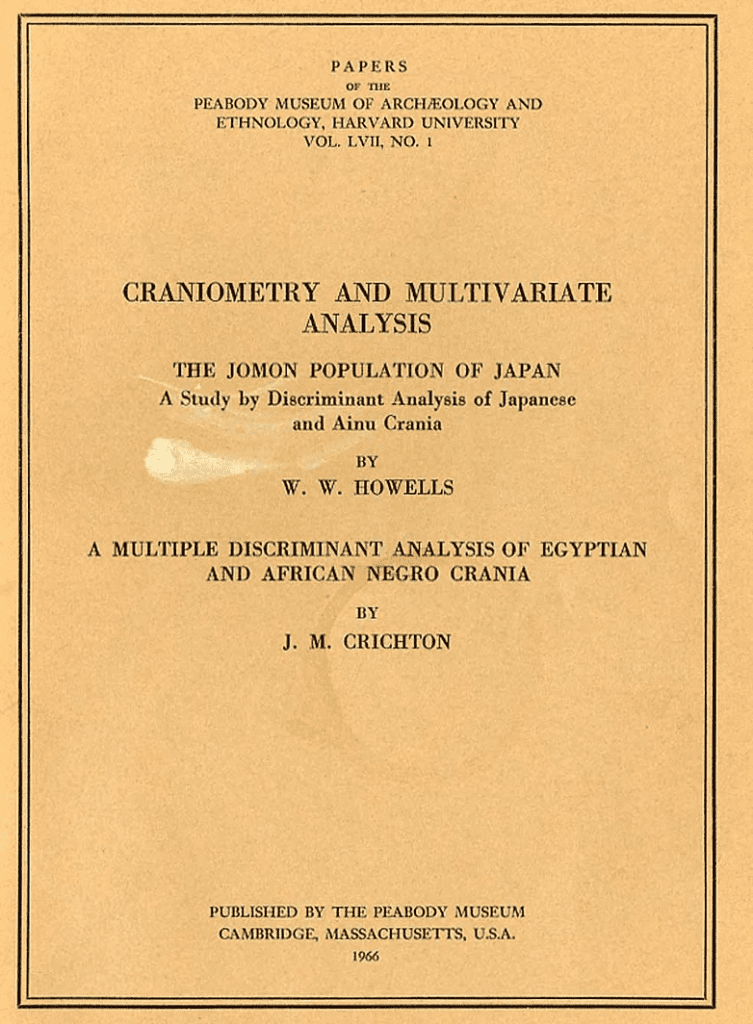

Michael Crichton’s multiple-discriminant analysis of Egyptian crania, carried out on an IBM 7090 computer at Harvard, was published in the Papers of the Peabody Museum in 1966

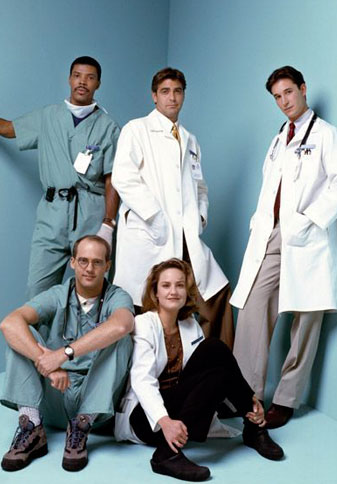

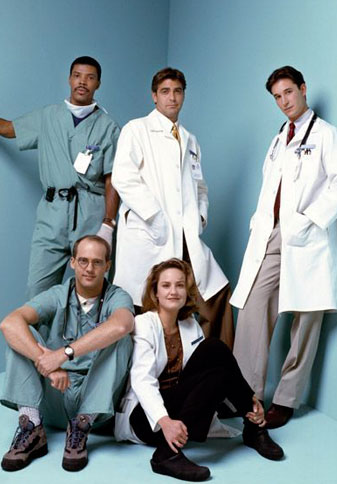

Projects Inspired by Michael Crichton's Time As a Doctor

I did write a TV script about the real world of doctors, but I discovered that people really don’t want to know anything straight about medicine. Their myths about that are very strong. People want their doctors to be Robert Young, not H.R. Haldeman – who would make a fine doctor, by the way. He tells people what to do, he believes what he says, and he gets the job done. I think the myths arose because people go to the doctor when they think they might die, and they esteem him in direct relation to the degree of that threat against their life.