Rising Sun

In His Own Words

In the early 1990s, I ate lunch almost every day at a Japanese restaurant in Santa Monica called Takanawa. Shortly after Rising Sun was published, the proprietor said to me that people were telling him to have nothing to do with me. They were saying terrible things about me. All this was because of my book, and he asked for a copy to read for himself.

A few days later he said he had finished it. He said that he thought the book was correct, but he said he understood why I was under attack. In fact, that seemed to be the wider view as well. I heard nobody say the book was inaccurate in its depiction of Japanese multinational practices in the late ’80s and early ’90s. But I heard lots of people say that I shouldn’t say things like that.

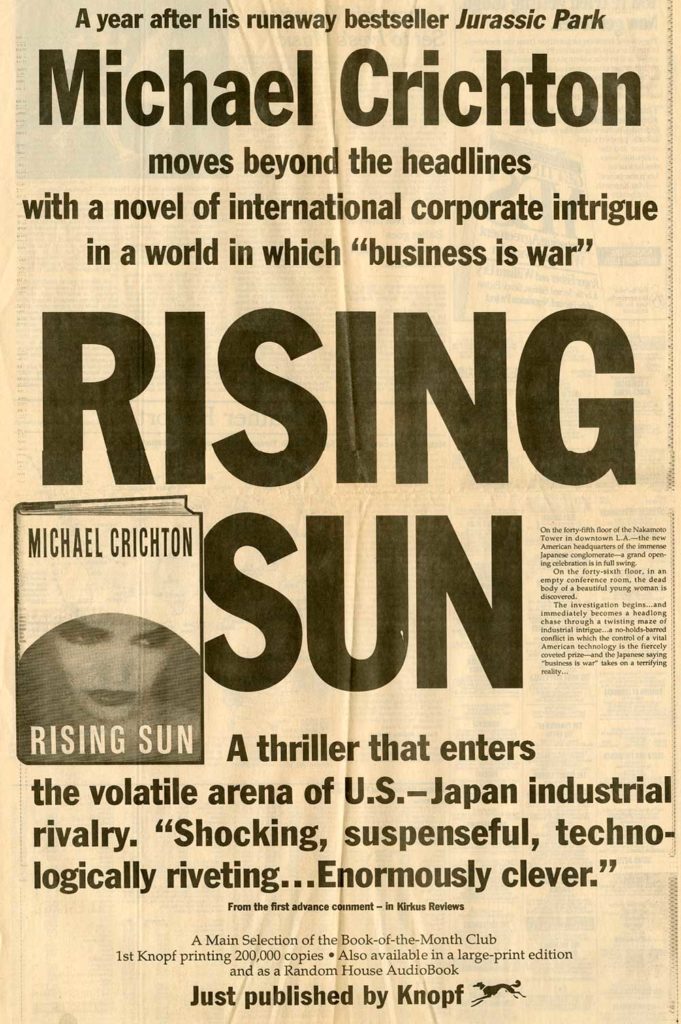

Synopsis

During the grand opening celebration of the new American headquarters of an immense Japanese conglomerate, the dead body of a beautiful woman is found. The investigation begins, and immediately becomes a headlong chase through a twisting maze of industrial intrigue and a violent business battle that takes no prisoners.

Passage 1

“It’ll help to be formal. Stand straight and keep your suit jacket buttoned at all times. If they bow to you, don’t bow back – just give a little head nod. A foreigner will never master the etiquette of bowing. Don’t even try.”

“Okay,” I said.

“When you start to deal with the Japanese, remember that they don’t like to negotiate. They find it too confrontational In their own society they avoid it whenever possible.”

“Okay.”

“Control your gestures. Keep your hands at your sides. The Japanese find big arm movements threatening. Speak slowly. Keep your voice calm and even.”

“Okay.”

“If you can.”

“Okay.”

“It may be difficult to do. The Japanese can be irritating. You’ll probably find them irritating tonight. Handle it as best you can. But whatever happens, don’t lose your temper.”

Passage 2

Suppose you work for a competing corporation, and you want to know what’s going on inside Nakamoto. You can’t find out, because Japanese corporations hire their executives for life. The executives feel they are part of a family. And they’d never betray their own family. So Nakamoto Corporation presents an impenetrable mask to the rest of the world, which makes ever the smallest details meaningful: which executives are in town from Japan, who is meeting with whom, comings and goings, and so on. And you might be able to learn those details, if you strike up a relationship with an American security guard who sits in front of monitors all day. Particularly if that guard has been subjected to Japanese prejudice against blacks.

“Go on,” I said.

“The Japanese often try to bribe local security officers from rival firms. The Japanese are honorable people, but their tradition allows such behavior. All’s fair in love, and war, and the Japanese see business as war. Bribery is fine, if you can manage it.”

Passage 3

“That’s not the point,” Connor said. “He’s not worried about legalities. He’s worried about scandal. Because that’s what would happen if we were in Japan.”

We came around the corner. Ishiguro was standing by the banks of elevators, waiting. We waited, too. There was an awkward moment. The first elevator came and Ishiguro stepped away for us to get on. The door closes on him bowing to us in the lobby. The elevator started down.

Connor said, “In Japan, he and his company could be finished forever.”

“Why?”

“Because in Japan, scandal is the most common way of revising the pecking order. Of getting rid of a powerful opponent. It’s a routine procedure over there. You uncover a vulnerability, and you leak it to the press, or to government investigators. A scandal inevitably follows, and the person or organization is ruined. That’s how the Recruit scandal brought down Takeshita as prime minister. Or the financial scandals brought down Prime Minister Tanaka in the seventies. It’s the same way the Japanese screwed General Electric a couple of years ago.”

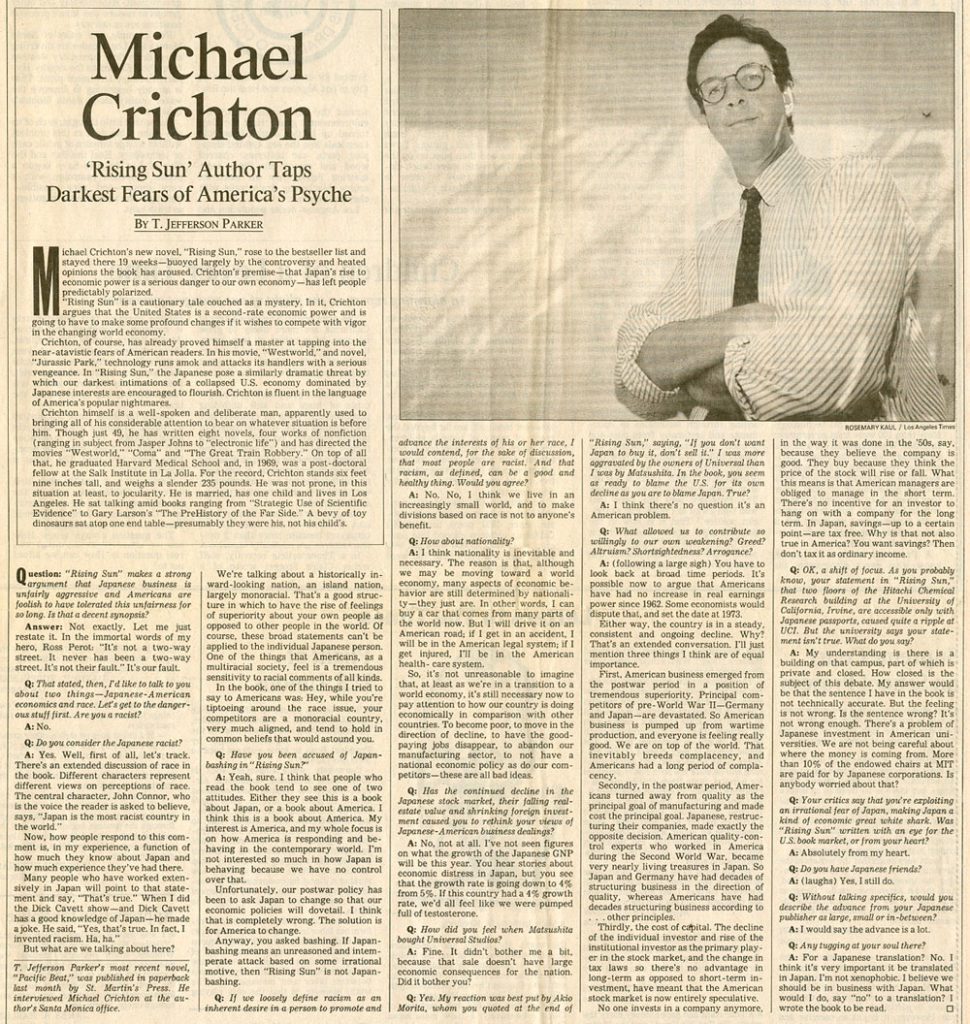

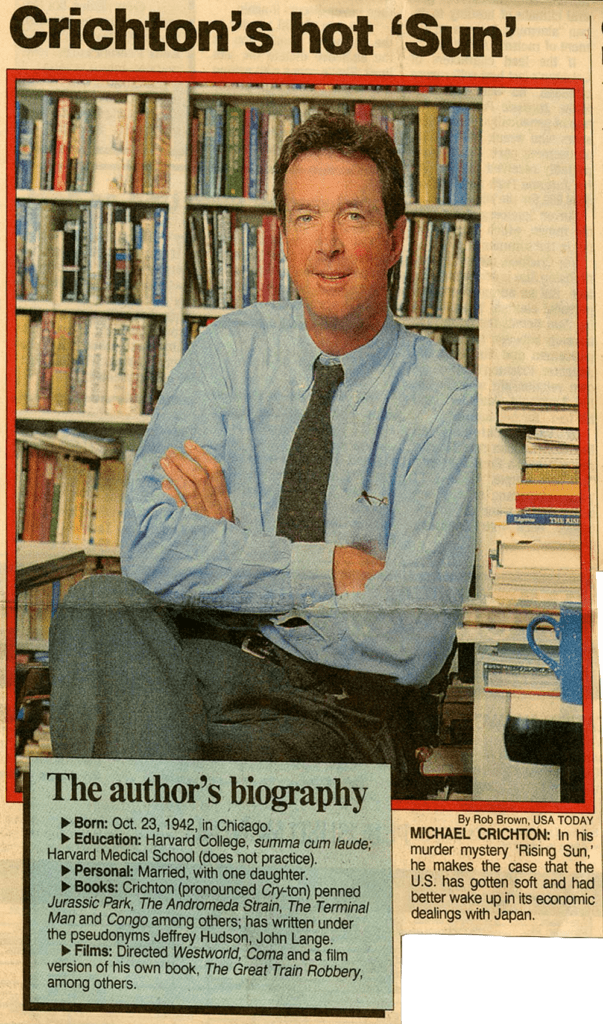

From the Archives

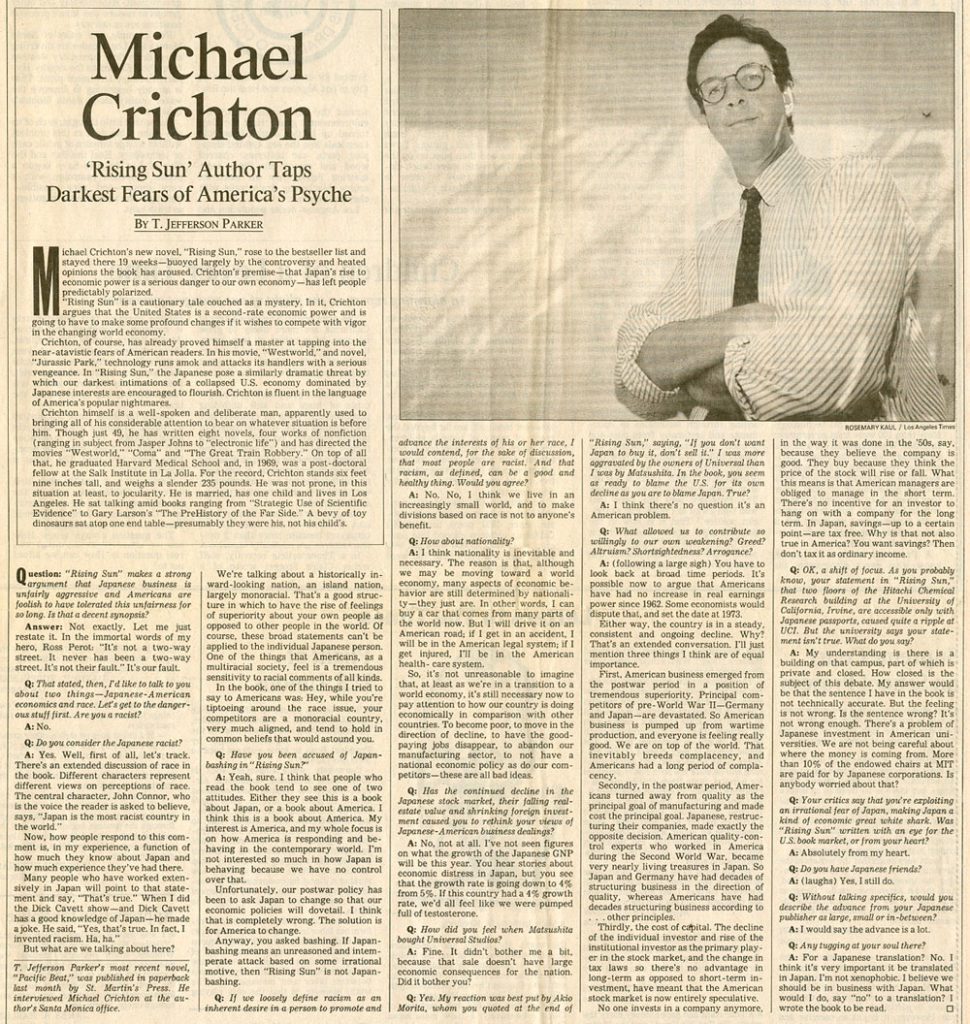

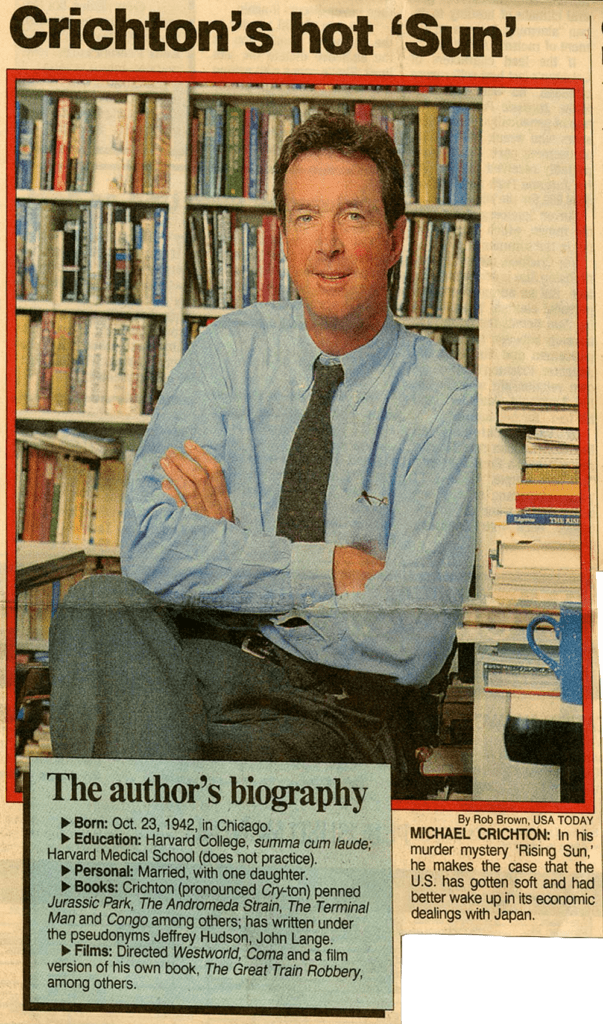

Author T. Jefferson Parker interviews Michael Crichton

In 1992, author T. Jefferson Parker interviewed Michael Crichton about Rising Sun for the Los Angeles Times. Michael Crichton talks about the controversy surrounding the book, expounds on the themes of the book and as was often the case speaks presciently about the state of the American economy. In this excerpt from the interview over twenty years ago, he talks about problems that are even more acute today:

“It’s possible to argue that Americans have had no increase in real earnings power since 1962. Some ecconomists would dispute that, and set the date at 1973.

Either way, the country is in a steady, consistent and ongoing decline. Why? That’s an extended conversation. I’ll just mention three things I think are of equal importance.

First, American business emerged from the postwar period in a postion of tremendous superiority. Principal competitors of pre-World War II – Germany and Japan – are devasted. So American business is pumped up from wartime production, and everyone is feeling really good. We are on the top of the world. That inevitably breeds complacency, and Americans had a long period of complacency.

Secondly, in the postwar period, Americans turned away from quality as the principal goal. Japanese, restructuring their companies, made exactly the opposite decision. American quality-control experts who worked in America during the Second World War, became very nearly living treasures in Japan. So Japan and Germany have had decades of structuring business in the direction of quality, whereas Americans had had decades structuring business according to … other principles.

Thirdly, the cost of capital. The decline of the individual investor and rise of the institutional investors as the primary player in the stock market, and the change in tax laws so there’s no advantage in long-term as opposed to short-term investment, have meant that the American stock market is now entirely speculative.

No one invests in a company anymore, in the way it was done in the ’50s because they believe the company is good. They buy because they think the price of the stock will rise or fall. What this means is that American managers are obliged to manage in the short term. There’s no incentive for an investor to hang on with a company for the long term. In Japan, savings – up to a certain point – are tax free. Why is that not also true in America? You want savings? Then don’t tax it as ordinary income.”

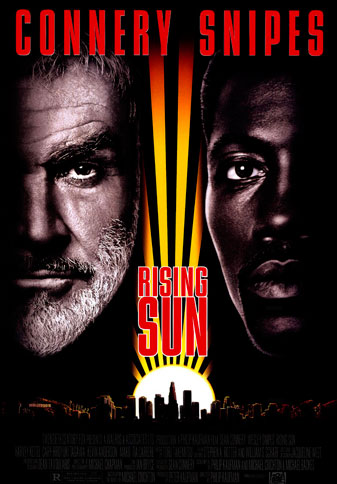

Rising Sun (Movie)

| Release Date: | July 30, 1993 |

| Running Time: | 2 hrs. 9 min. |

| MPAA: | R |

| Director: | Phillip Kaufman |

| Screenwriter: | Michael Crichton, Michael Backes, Philip Kaufman |

| Based on the Novel By: | Michael Crichton |

| Studio: | 20th Century Fox |

| Starring: | Sean Connery, Wesley Snipes, Harvey Keitel, Cary-Kiroyuki Tagawa, Kevin Anderson |

Rising Sun was one of the Top 20 movies of 1993

Book Covers